Nothing explains fashion’s stranglehold on contemporary culture than Instagram, as the popular social media platform is flooded with beautiful people, donning both branded and unbranded clothing. Whether sponsored or based on the influencer’s own caprice, the very volume of uploads can deem Instagram a barometer of minute-by-minute popular haute couture or streetwear.

In the not-so-distance past, the perception of “streetwear” was once a (perhaps) culturally appropriated amalgam of urban style, turning standard, comfortable, daily activewear into vibrant, deconstructed must-haves. But in its simplest definition, streetwear can be explained as clothing one might wear outside of the home, and, as items to be “seen” in.

Charles Frederick Worth, founder of House of Worth.

The rush to present the public with labeled, coveted clothing style may trace to 1858 when Charles Frederick Worth was the first to sign his name to his designs. Haute couture is believed to have its origins in Worth, an English textile merchant worker, who in 1851 approached Maison Gagelin-Opigez et Cie, a Paris-based luxury fabric company, about harnessing his knowledge of fabrics and dressmaking to design and produce his own garments. It was a revolutionary idea, as women as recent as the 19th century had designed their own dresses. Since his clients included royalty, it’s unsurprising that society’s finest were lining up to own and wear a Worth. And from this desire to put on clothing with its designer’s name, fashion — and the subsequent fashion marketing — was born.

Thus, starting with the Victorians, “name brands” became a “thing,” and for several decades, a “thing” reserved for the very wealthy. Still the symbol of wealth today, it may surprise those swinging LV Speedys, that Louis Vuitton founded the luxury French fashion house in 1854. It’s hard to imagine Vuitton (the designer, not the brand) could have conceived the line’s “Mule Waterfront,” essentially a $605 pool slipper, or the $965 Rivoli Sneaker boot (which actually retails for more than LV’s all-leather loafer).

Empress Eugénie de Montijo, the last empress of the French, who employed Charles Frederick Worth as her primary dressmaker, and Monsieur Louis Vuitton as her luggage-maker: helping both icons achieve their stardom.

House of Worth ball gowns (ca. 1892), dense and rich with silver bead embellishments and crystal embroidery.

This same concept carries surprisingly well into the modern era, albeit in new forms. Fashion houses such as Chanel and Christian Dior became haute couture establishments because they met specific criteria: designing made-to-order garments for private clients through multiple fittings, having a full-time staff of at least 15, and presenting their collections of at least 50 original designs to the public at least twice annually. Luxury fashion was once marked by luxe fabrics like rich velvets, intricate lace, and extravagant embroidery, as well as fine cut and tailoring. Today there is some carry-over, but even luxury insiders of the French-American Chamber of Commerce (FACC) admit that the definition of “luxury” has become more difficult to pin down.

Grace Kelly with her namesake Kelly bag by Hermes.

Romy Schneider outfitted by Coco Chanel.

Iconic Off-White belt on the Off-White Diag Printed Leather Belt Bag.

As the younger generations gain spending power and become the dominant demographic purchasing luxury fashion, their priorities (Instagram and all) are being taken seriously by major fashion houses. Millennials and Gen Z already account for 30% of global luxury sales, and they’re on pace to hit 45% by 2025, according to the consulting firm Bain & Company. Young shoppers are now more interested in “brand” than craftsmanship or historical value. ”The emphasis has gone from quality and craftsmanship into the uniqueness of the product,” Balenciaga’s creative director, Demna Gvasalia, told the Financial Times. No singular recent event exemplifies this point more than Louis Vuitton’s appointment of Virgil Abloh, Kanye West’s creative director and the founder of streetwear brand Off-White, as Men’s Artistic Director.

Image from the runway show of Louis Vuitton Fall-Winter 2019 Collection by Virgil Abloh.

Young shoppers are now putting more value on items that make them stand out than ones with a storied heritage. In the case of Abloh’s belt, the low-end material isn’t what you might traditionally associated with high fashion, but customers aren’t shelling out hundreds for the fabric—they’re buying entrance into a fashion club that only in-the-know insiders can access.

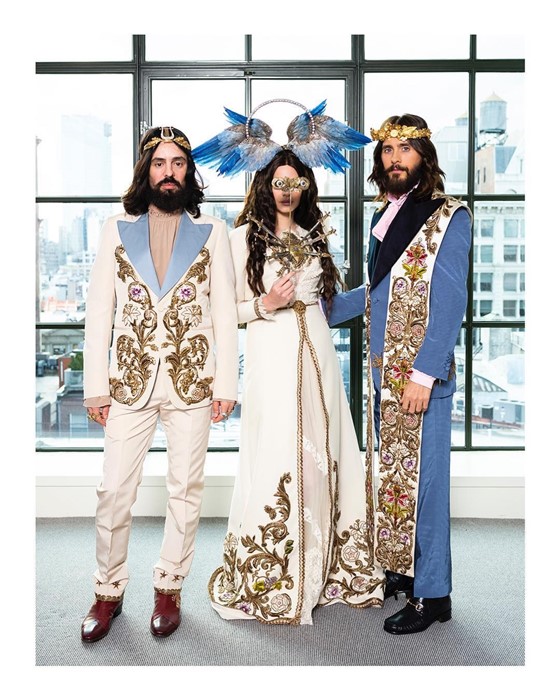

Alessandro Michele’s eccentric excess for Gucci.

Alessandro Michele, Lana del Rey, and Jared Leto in custom Gucci attire at the Heavenly Bodies Met Gala.

Likewise, in 2015 Gucci took on a dramatic new look–what can be called a ‘rebellious chic’–when designer Alessandro Michele was appointed as the new creative director. Paying attention to the millennial generation and its prioritization of “unique” fashion objects instead of luxurious, Michele combined extravagant, bold fantasy color palettes with a mix of low-end materials like corduroy and fake furs. The new Gucci was creating luxury for the everyday. Similarly, in 2015 the house of Balenciaga began transitioning its designs to an ‘oversized’ style and especially with athletic, sportswear details. The brand took notes from young streetwear designers, especially sleek Scandanavian fashion. Fendi, too, became more playful in recent years as it turned towards streetwear. Major design labels are hedging their bets that the future of luxury is in logo-printed tees, chunky sneakers, and printed sweats.

In the tech age, fashion houses have also had to adapt to a ‘sharing economy.’ With the rise of services like Uber for ridesharing without buying the car and Netflix for streaming without buying DVDs, Millennials can now rent designer fashion with popular services like Rent the Runway. The emphasis has been placed on the high-end look, but for cheap.

Fashion influencer and blogger Camila Coelho’s casual street-inspired airport look.

If this trend is shocking to you, there are some positive features to the rise of streetwear. Fashion is no longer an exclusive club only available to a handful of people of the upper echelons of society with exceptional tastes. Now fashion is inclusive to everyone and is present all the time. The industry is also paying more attention to the non-white and non-wealthy, as younger luxury consumers are more diverse, and the financial and cultural power of hip-hop/rap and streetwear grows.

Dress historian James Laver wrote of fashion from the 1840s: “The old, rigid society-mould [sic] was visibly breaking up… For the young, there was a new breath of freedom in the air, symbolized both by their sports costumes and by the extravagance of their ordinary dress. It was perfectly plain that the Victorian Age was drawing to its close.” Are we experiencing yet another break-up of rigid, pretentious, dusty fashion traditions? History is cyclical, and so too do trends cycle back and forth into fashion eternal.