Zen Buddhists have a popular mantra with spiritual, aesthetic, and practical wisdom: “form is emptiness, emptiness is form.” Emptiness here is not only a spiritual state–a meditative realization–but also an aesthetic ideal, also called mu 無; without, nothing, or nothingness. You may recognize mu in unlikely and contemporary places: the popular Japanese stationary and lifestyle store Muji (無地), which translates to “plain/no pattern.”

In eastern traditions, as you can see, aesthetics are often linked to world view and philosophy. The aesthetic concept aptly used for Japanese tea ceremony, in all its traditions, protocols, and decorum, is wabi-sabi: a rarified beauty that is imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete. It is the penultimate beauty in rawness, nature, and simplicity: an aesthetic with profound poetic wisdom.

In the contemporary art and design world, these aesthetic concepts have familiar manifestations. A Japanese-inspired style values simplicity, minimalism, earthen materials and organic forms––think washi-paper lanterns and rustic raku-ware tea bowls. Zen and eastern aesthetics have helped catalyzed much conceptual art and American avant-garde literary and philosophical movements in the contemporary West. And the contemporary artists following in these aesthetic traditions create work that is often quietly sophisticated, yet meditative and powerful, with wide-reaching appeal.

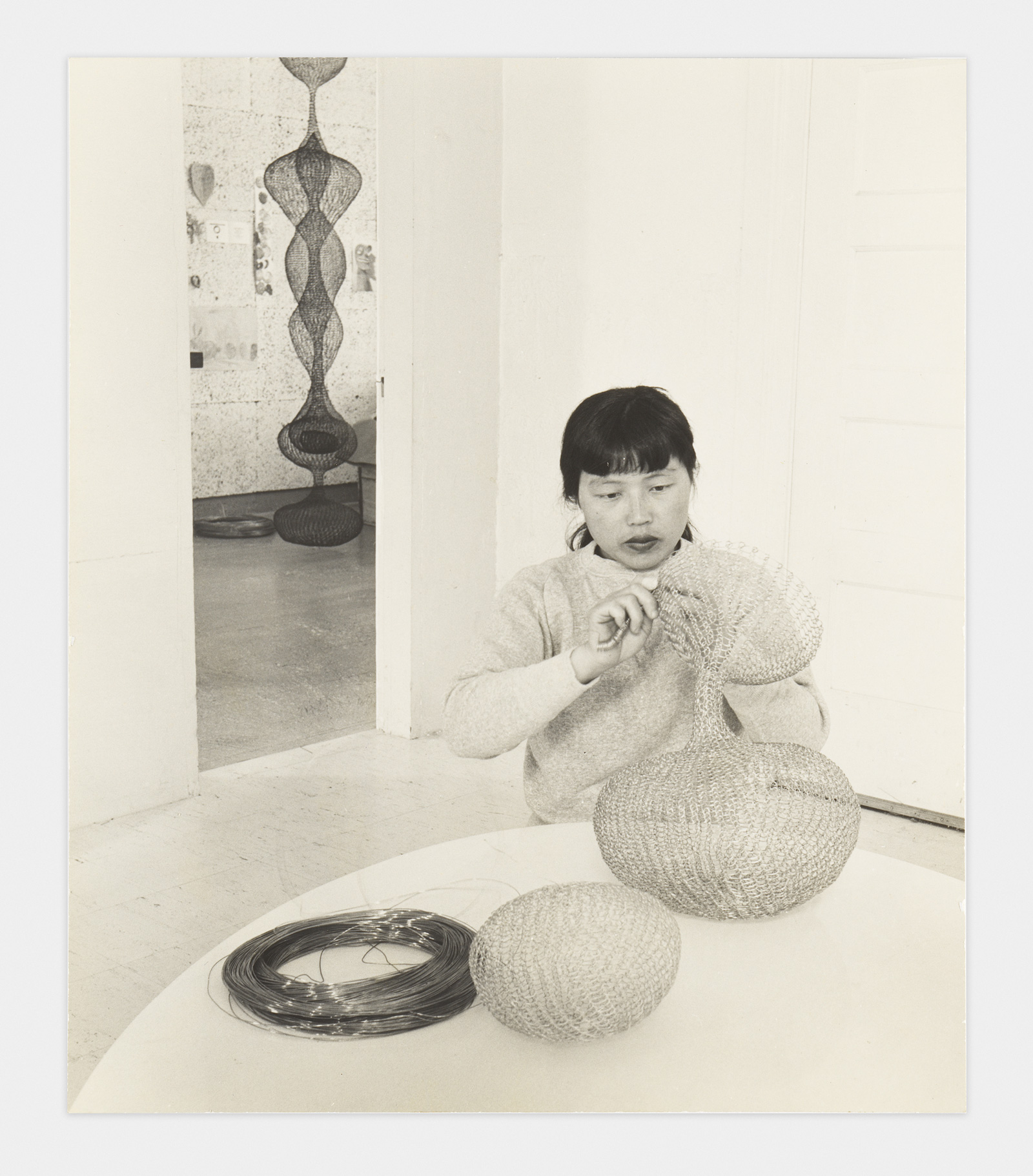

Ruth Asawa’s ouvre stands as a true tour-de-force of American Minimalism. Born in rural Norwalk, CA, to Japanese immigrants in 1926, Asawa continues to be a bold, fascinating character whose artistic practice constantly triumphed against formidable odds. Asawa’s family farming business, and indeed Asawa’s early life, was uprooted by their detainment in Japanese internment camp during World War II. After the war, Asawa sought a teaching degree from Milwaukee State Teachers College but after being met with discrimination, enrolled in the prestigious Black Mountain College in North Carolina, studying under such prominent artists as Buckminster Fuller and Merce Cunningham. And indeed, Asawa’s practice is the apt answer to the work of such male modernist counterparts as Alexander Calder and John Cage.

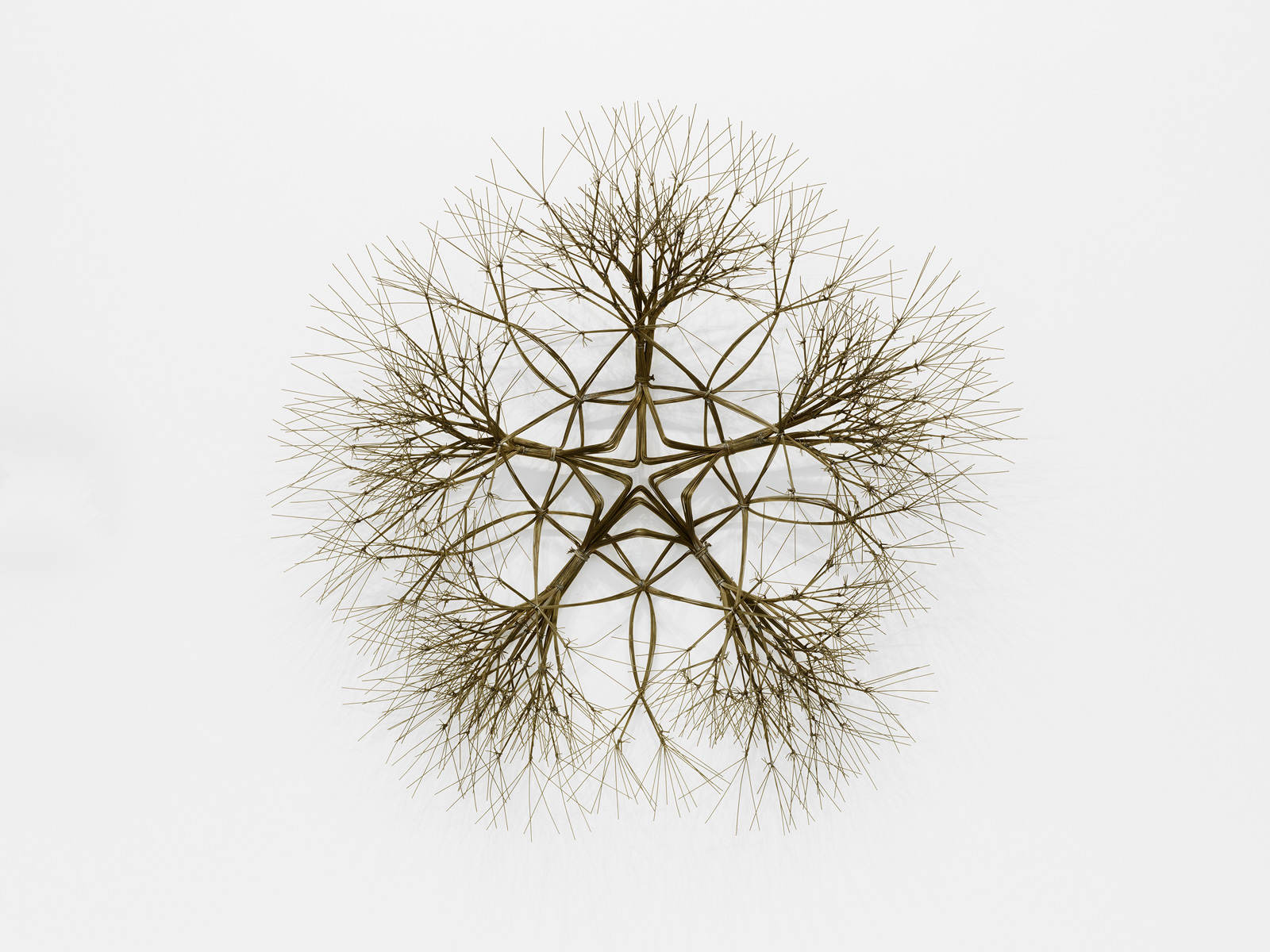

Asawa developed her signature style at the age of twenty-one, inspired by native Mexican basket-weaving techniques. She was acclaimed for her looped wire sculptures, in which she crocheted galvanized wire into complex biomorphic and vegetal forms, elegantly suspended from the ceiling. These works, with their intricacy, denoted a gossamer lightness and transparency, and explored the creative force of the continuous line as a sculptural form. Asawa developed her practice further with her tied wire sculptures, which she referred to as “trees” or “branching forms,” beginning as a center stem of hundreds to thousands of wires branched into multi-point organic or geometric forms. Asawa’s sculptures are a clear nod to the natural world and evocative of her Zen roots with their subtlety and power, combining refinement of form with sheer emotive force.

“My curiosity was aroused by the idea of giving structural form to the images in my drawings. These forms come from observing plants, the spiral shell of a snail, seeing light through insect wings, watching spiders repair their webs in the early morning, and seeing the sun through the droplets of water suspended from the tips of pine needles while watering my garden.” – Ruth Asawa

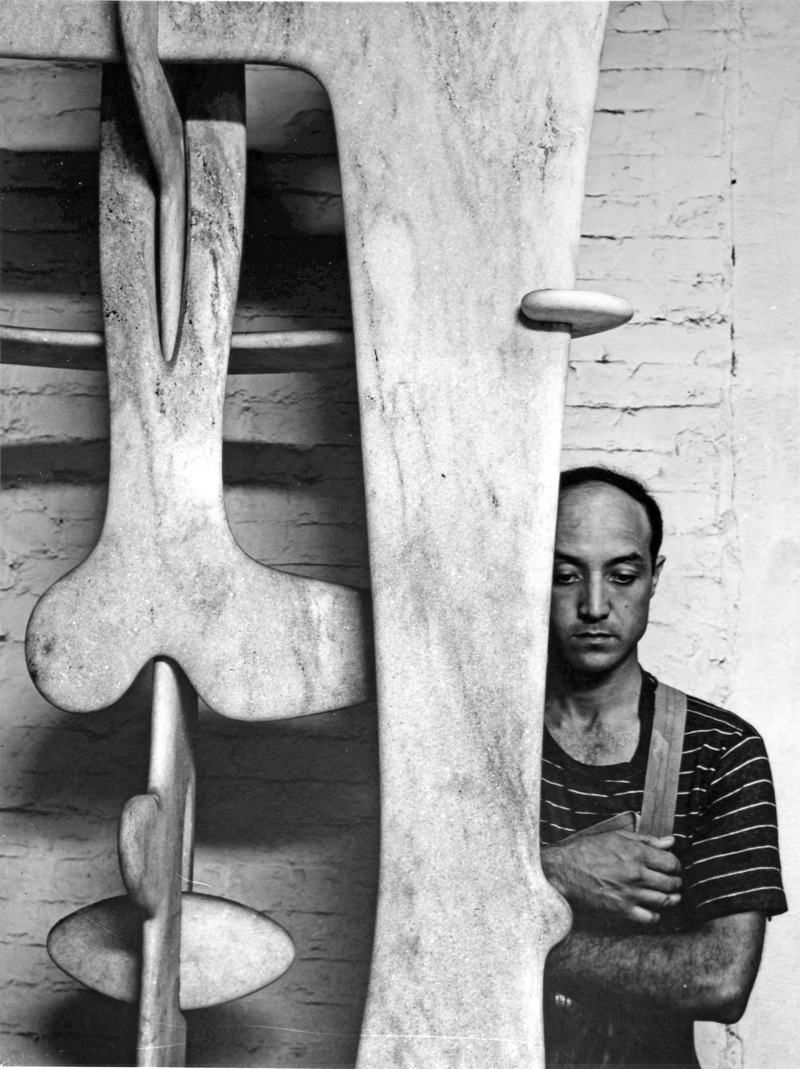

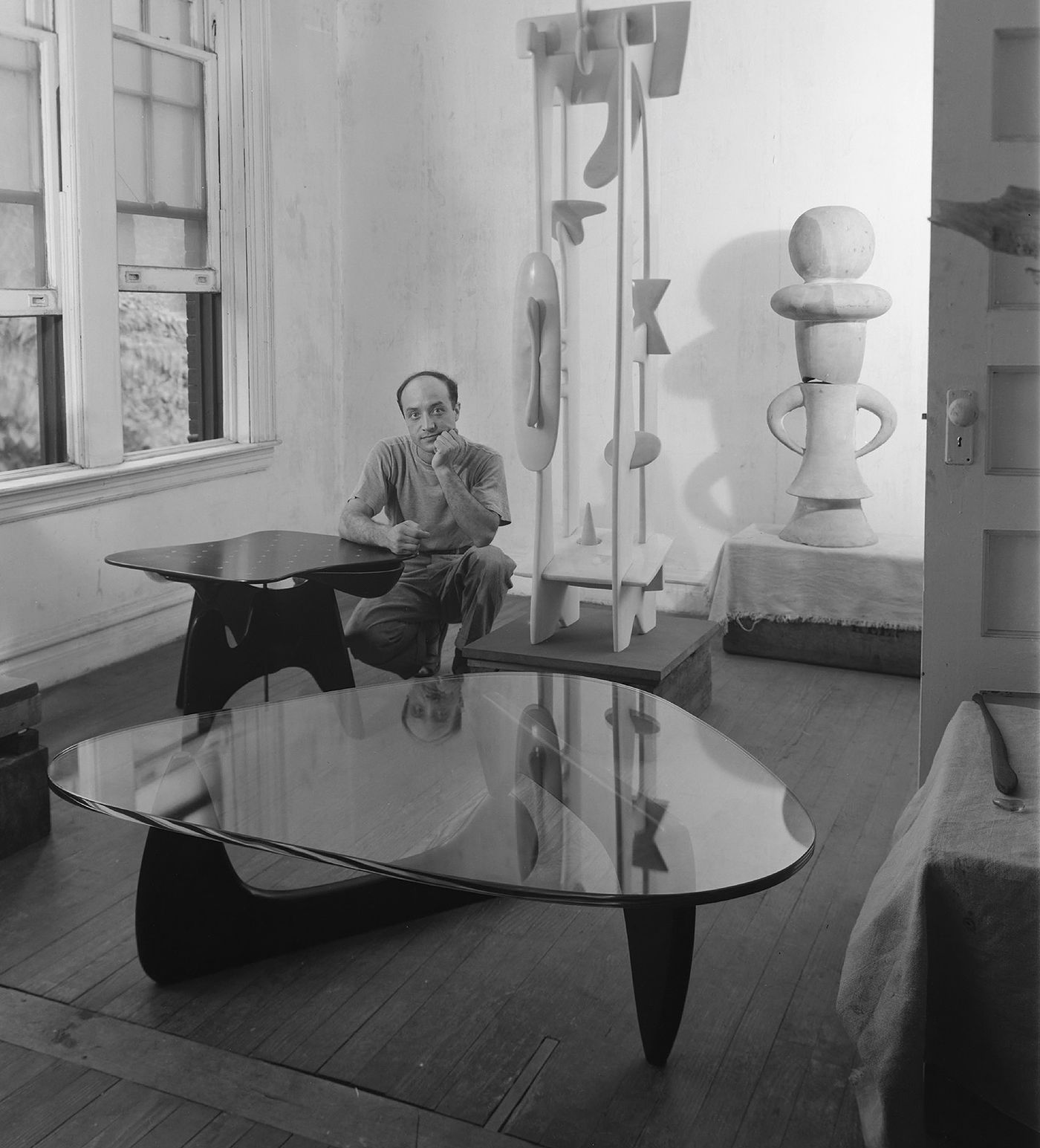

True artistic mastery is exemplified in the intimacy with which the artist understands their medium. Michelangelo is said to have deeply understood marble in this way. Another such artist is Isamu Noguchi, whose comprehensive opus shaped art and design for the annals of American modernism. His extraordinary breadth of interest made him a pioneer of stone and marble, bronze, cast iron, aluminum, and terracotta, manifested in sculpture, furniture design, theater props, architectural projects, gardens and public spaces. Noguchi was born in 1904 to a Japanese poet and his Irish-American editor in Los Angeles, CA, the illegitimate result of a passionate tryst. His mother Leonie Gilmor, aware of Japanese discrimination in the United States, raised Noguchi in Japan with little assistance from Noguchi’s father, who had started his own separate family in Japan. Noguchi was often puzzled with his racial identity, and wrote in his autobiography, “With my double nationality and double upbringing, where was my home? Where my affections? Where my identity? Japan or America, either, both–or the world?”

In fact, his biracial identity would eventually spawn his iconic artistic philosophy: an unprecedented combination of Western modernism and Japanese aesthetics. As the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, Noguchi studied under Constantin Brancusi in Paris during the spring of 1927 as his studio assistant. Noguchi ruminated often on Japanese gardens and the primordial force of stone. Coupled with 20th-century Euro-American modernist influences and abstract forms, Noguchi gained acclaim for his biomorphic stone sculptures, which were at once sophisticated and sensual, yet highly experimental in form and space. His furniture designs continue to be widely sought-after, like his Akari Light Sculpture washi-paper lanterns and iconic coffee table with their soft-edged, clean aesthetic. Transcending the boundaries of art and space, Noguchi often collaborated artistically with choreographers and dancers like Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham. Close friend and collaborator of Noguchi Buckminster Fuller believed Noguchi had become “the most comprehensive artist without peer in our times.” His works can be found in private and public collections throughout the world, gracing Rockefeller Center, Manhattan Plaza, UNESCO headquarters of Paris, the Yale sculpture gardens, and many more.

“To search the final reality of stone beyond the accident of time, I seek the love of matter. The materiality of stone, its essence, to reveal its identity–not what might be imposed but something closer to its being. Beneath the skin is the brilliance of matter.” – Isamu Noguchi

Modern Japanese design concepts combine a rich mix of traditional practices and modern aesthetics, decorative and minimalist while implementing modern technologies and materials. Shigeru Ban is a Japanese architect renowned for his humanitarian disaster-relief architecture and radical experiments in design using lightweight, unconventional, and ecologically responsible materials. His signature style manifests in soaring organic structures and gracefully undulating grids, sophisticated and clean in their aesthetic yet implementing materials as simple as paper, bamboo, and even cardboard (which he calls “improved wood”). Some of his most iconic projects are his paper tube structures, which are fire and water-proof, and helped him earn such accolades as the prestigious Pritzker Prize for architecture in 2014.

Ban was born in Tokyo in 1957 and excelled in arts, traditional carpentry, and design at a young age. In 1977, Ban moved to California to study English and enrolled at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arch) before transferring to the prestigious Cooper Union. His groundbreaking structures, heavily influenced by traditional Japanese architecture, are not only beautiful but fast, economic, and sustainable. Working with the U.N., Ban’s relief organization Voluntary Architects’ Network (VAN) has helped create emergency shelter and permanent homes using regional materials following natural disasters in Nepal, Haiti, India, Japan, Sri Lanka, China, Italy, New Zealand, and other countries. “Refugee shelter has to be beautiful,” Ban told TIME Magazine, “Psychologically, refugees are damaged. They have to stay in nice places.” His TIME profile refers to him as an architect who “wants beauty to be attainable by the masses, even the poorest.” His robust portfolio of creative design and housing solutions have graced public, private, and humanitarian spaces all across the globe.

“I was interested in weak materials. Whenever we invent a new material or new structural system, a new architecture comes out of it.” – Shigeru Ban

As a nation of immigrants, the history of American art is continuously being rewritten in more diverse terms. And indeed, the global scope of artistic innovators widens in all directions, Eastward as well as Westward.