“How should an architect situate their work against the natural environment?” In the 21st century, this question has been asked with a renewed urgency. The most lauded architectural projects today need not only be aesthetically beautiful and industrially sound: they consider their natural surroundings and are fully integrated into their natural environment, acting as a part of a larger ecosystem.

Curator, writer, and designer William Myers explains that today there is increasing pressure on designers to recognize our responsibility to protect fragility of nature and our responsibility for future generations. Designers are being asked to pivot their design philosophies, making attempts to consider the natural circumstances around their projects and harness biological processes of the environment: ideally resembling what happens in ecosystems, in which waste is eliminated and anything that goes into one process can safely enter another one in a closed-cycle manner, or put back into the environment.

Internationally renowned architect and urbanism theorist Diana Agrest is one such figurehead who is shifting modern discourse about the built versus the natural world, by considering them as interchangeable instead of in opposition. With her advanced research studio at The Cooper Union, where Agrest is a long-time professor, she’s addressed the absence of nature from urban discourse for almost 50 years. In her newest book Architecture of Nature/Nature of Architecture, Agrest collects graduate work from her studio at The Cooper Union: projects in which geological forces are represented with the same attention to detail and tools as those paid to architecture, considering nature as an object of study within the field of architecture. Agrest’s unique architectural philosophy seeks a liberation of nature from binary sets of opposition in which it has traditionally been defined: man vs. nature, man vs. culture, nature vs. architecture, and so on. In this way, it becomes itself a free radical object of study across time and space in its relationship to architecture, and able to transform the discipline positively. Her book posits speculations on a number of contemporary topics, such as architecture seen in line with the Gaia hypothesis and utopian urban design theory.

Internationally renowned architect and urbanism theorist Diana Agrest is one such figurehead who is shifting modern discourse about the built versus the natural world, by considering them as interchangeable instead of in opposition. With her advanced research studio at The Cooper Union, where Agrest is a long-time professor, she’s addressed the absence of nature from urban discourse for almost 50 years. In her newest book Architecture of Nature/Nature of Architecture, Agrest collects graduate work from her studio at The Cooper Union: projects in which geological forces are represented with the same attention to detail and tools as those paid to architecture, considering nature as an object of study within the field of architecture. Agrest’s unique architectural philosophy seeks a liberation of nature from binary sets of opposition in which it has traditionally been defined: man vs. nature, man vs. culture, nature vs. architecture, and so on. In this way, it becomes itself a free radical object of study across time and space in its relationship to architecture, and able to transform the discipline positively. Her book posits speculations on a number of contemporary topics, such as architecture seen in line with the Gaia hypothesis and utopian urban design theory.

“Nature has played a key role in the history and theory of Western architecture, appearing as a constant motif in architectural texts from its very beginnings with Vitruvius to Alberti and all the way to Le Corbusier’s Radiant City. It is seen as a basic element in the development of architectural theory and principles, but this interaction takes a prominent position at the present moment.” – Agrest in an interview with Archinect

Over time, biologically-minded architecture has shifted from looking towards nature as a visual model, to studying its functionality. “Bio-inspired architecture” is a broader term that considers nature’s functions in scientific understanding, how its processes can be studied towards architectural innovations in sustainability.

In 1991, architect Mick Pierce ran into a design challenge when an investment group in Harare, Zimbabwe requested him to design a shopping center and office block, but without a power-hungry air conditioning system: a seemingly impossible task in Zimbabwe’s hot climate. In response, Pierce turned to an unlikely inspiration: the ingenuity of the tiny termite and its towering mounds. The Eastgate Centre in Harare was designed to self-cool and ventilate in the same way. Moving away from the “big glass block” design for offices, which are expensive to maintain at a comfortable temperature, Pierce created an architectural marvel that achieves 90 percent passive climate control by taking cool air into the building at night and expelling heat throughout the day. Like the soil inside a termite mound, the concrete bricks of the Centre have a high thermal mass, meaning they can absorb heat without changing temperature. Several small windows as opposed to fewer large ones minimize the building’s heat absorption, like the tiny holes throughout termite mounds that allow the colony to regulate internal temperature. When temperatures rise warm air is ventilated upwards and released through the rooftop chimneys of the building. The Eastgate Centre has become a global landmark for sustainable, biologically-inspired architecture and is the first of its kind to use natural biomimetic cooling at such a level of sophistication and efficiency.

Observing the graceful flutter of a butterfly’s wings, sunflowers following the sun throughout the day, and trees swaying in the wind, one thing is clear: the natural world is in constant flux and fluid motion. For human structures which are static and seemingly indifferent to their environment, is it possible to integrate nature’s sense of dynamism architecturally? Spanish-born architect Santiago Calatrava’s designs suggest stylized natural objects—waves, wings, or sun-bleached skeletons, often rows of white concrete ribs curved into sweeping parabolic arches, often inspired by nature but featuring a combination of organic forms and technological innovation. Calatrava’s tour de force design is arguably his elegant additions to the Milwaukee Art Museum, especially the building’s most eye-catching feature: the Burke Brise Soleil, a moveable sunscreen with a 217-foot wingspan that unfolds and folds throughout the day. The 90 ton screen, is operated through movable steel louvers lifting the 217-foot wingspan. This iconic building, often referred to as “the Calatrava,” received the 2004 Outstanding Structure Award from the International Association for Bridge and Structural Engineering.

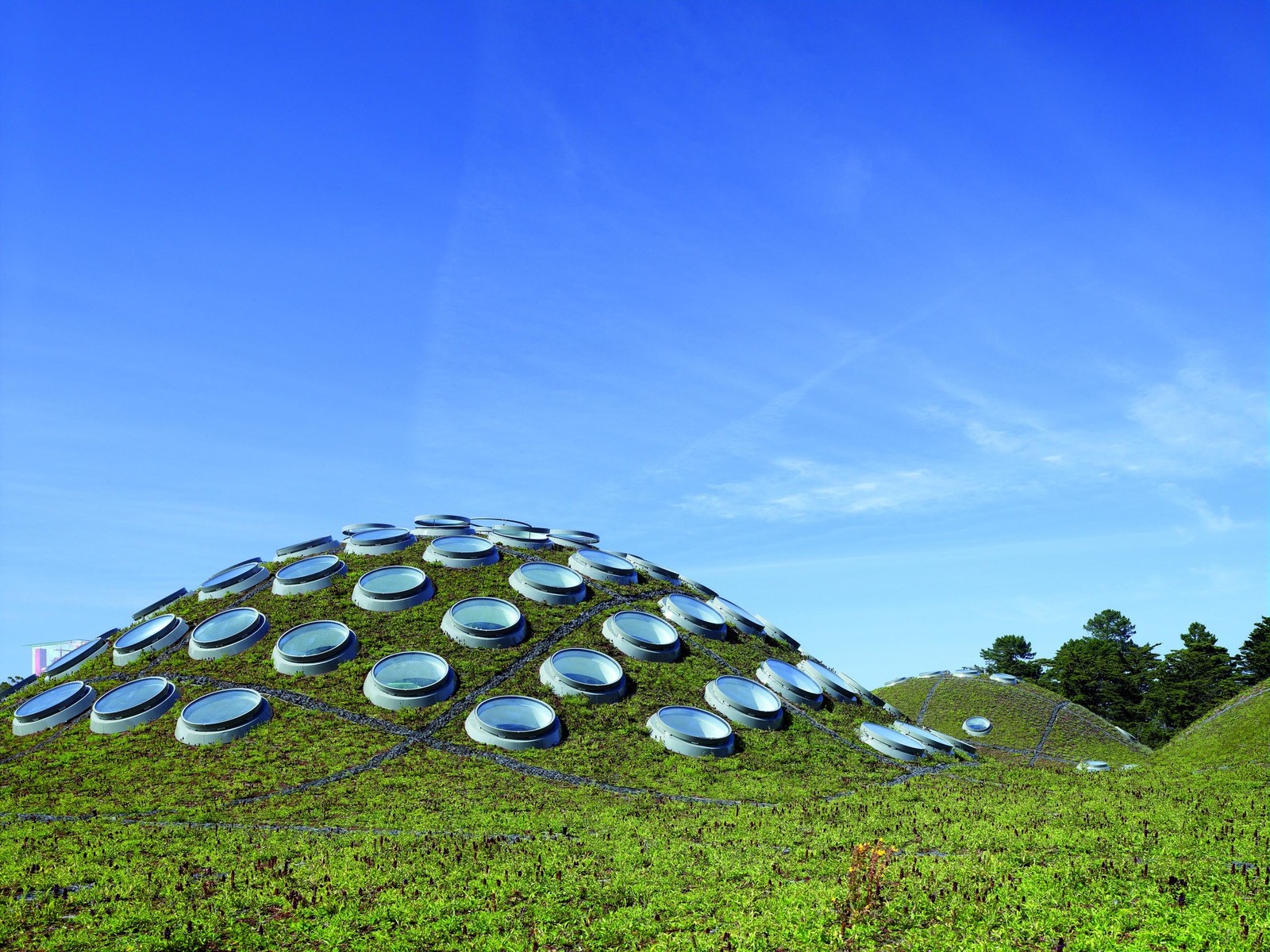

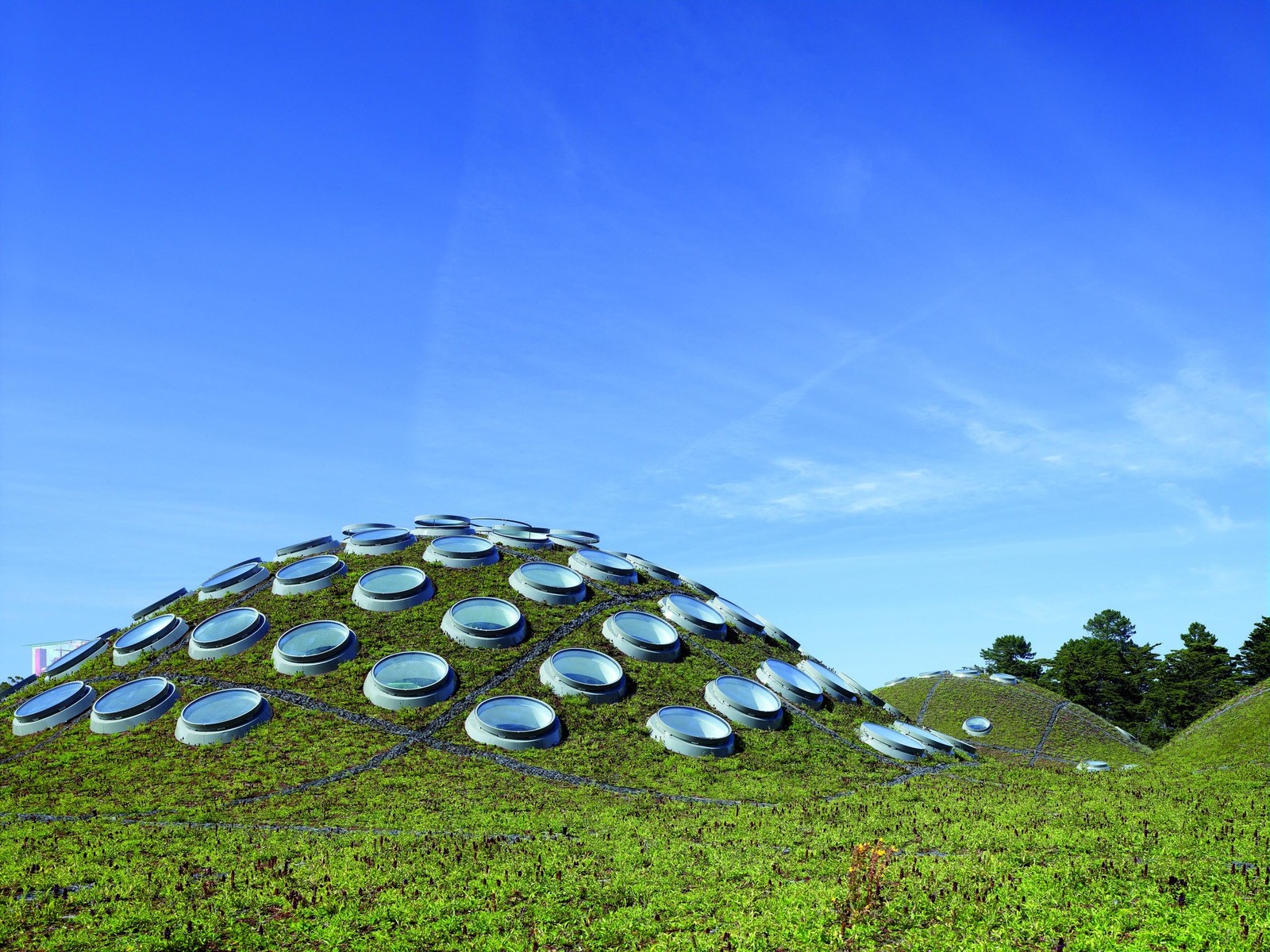

Few contemporary architects have the level of accolades that Renzo Piano does: an Italian architect known for his high-tech public commissions, like the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, the Kansai International Airport Terminal in Osaka, the Modern Wing of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Menil Center, and the San Nicola Soccer Stadium in Italy, just to name a few. One of his most celebrated projects is his green architectural project, the new building for the California Academy of Science in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. Completed in 2008, the building combines exhibition space, education, conservation and natural history, as well as housing the Institute for Biodiversity Science and Sustainability’s research arm. Its most striking feature is the large green roof, which has several sustainability features. For its design, Renzo Piano was inspired by San Francisco’s seven major hills: Telegraph Hill, Nob Hill, Russian Hill, Rincon Hill, Mount Sutro, Twin Peaks and Mount Davidson. The living and breathing roof was planted with 1.7 million California native plants, serving as a habitat for local birds and butterflies. Its six inches of soil substrate act as natural insulation and prevent stormwater runoff from carrying pollutants into the ecosystem. Like a natural rolling field, the roof is flat at its perimeter and undulates into hills as it moves towards the center. The two main domes house the planetarium and rain forest exhibitions, speckled with skylights automated to open and close for ventilation. A solar canopy around the perimeter of the Living Roof contains 60,000 photovoltaic cells that supply power to the building. Between this, the glass fixtures, soil roof, and other sophisticated thermodynamic features, the structure is incredibly energy efficient and self-sustaining, helping to reduce the city’s carbon footprint and preserve natural resources. The mission of the project, Renzo Piano stated, was to “lift up a piece of the park and put a building under.” And that it does, blending seamlessly into Golden Gate park’s stunning natural vista.

“One of the great beauties of architecture is that each time, it is like life starting all over again.” – Renzo Piano

However, Renzo Piano was certainly not without critics of his style. Many of his projects, including the Centre Pompidou, were exceedingly controversial. Italian colleagues often cited flaws in how nonurban his projects appeared, with no conventional architectural elements, spatial sequence, or architectural presence. That so, these same critiques are what makes Renzo Piano’s headquarters so special, carrying on the same values of his many cutting-edge and environmentally conscientious projects. Built in 1989, the Renzo Piano Building Workshop in Punta Nave references the shapes of coastal Ligurian greenhouses: natural light and gradually sloping terraces filled with greenery open to the sea, not separate from but in communion with the landscape. Its walls are almost entirely natural in their construction of pink stucco, fieldstone, and laminated timber beams. The only structurally inorganic elements visible are the steel posts holding the beams together as well as the solar-cell controlled levers and blinds that shade the roof and glass wall. Few contemporary buildings, especially office complexes, are able to so fully integrate with their natural environment, creating a constantly-changing space and an ever-inspiring freshness.

In a similar unobtrusive vein, China’s Wenchuan Earthquake Memorial Museum takes form within its placid landscape, entirely subterranean and preserving the natural integrity of the valley. In the wake of a massive earthquake in 2008 in China’s Sichuan province, the Chinese government commissioned the architecture faculty of Tongii University to hold a competition among staff for the design of a memorial for the 70,000 lives lost and 18,000 missing at the quake’s epicenter in Wenchuan. The question then stood: how best to respectfully memorialize such a momentous tragedy, in a way that retells its history thoughtfully? Designer Cai Yongjie won first prize and conceived of a subterranean museum and monument, taking the form of an abstract fissure in the earth. Lined with CorTen steel, the huge walls take on an earthy patina to remind visitors of the entropic power of natural phenomena. Similarly to Piano’s Science Academy, the Earthquake Memorial is roofed with gently sloping green space, equipped with an anti-seismic system based on rubber shock absorbers. The rift design relies on layers of reverberating symbolism––from the ruptured earth of the quake, to the wounds in the hearts of survivors, and the chasms for those who were lost or missing.

The colonialist outlook of man conquering the wildness and savagery of nature seems long gone. especially as we build our cities and institutions, a separatist design philosophy has seemingly fallen out of fashion in favor of a responsive and subdued approach, prizing effective use of the surroundings and careful consideration of natural circumstances. Architecture critic Philip Jodidio states that “the most interesting buildings of today are, almost without exception, respectful of the environment, sustainable and designed to consume the least energy possible.” Indeed, the most cutting-edge and respected designs are noticeably absent of “unsustainable extravagance,” or the struggle for human and architectural permanence erected in harsh stones and steels. Instead, they might change with the seasons, integrate natural elements, barely noticeable in a larger landscape, or simply exist in harmony with it, as yet another feature of the environment.