The contemporary art markets and scenes, in all their voracity for provocative, moving, and innovative work, casts its eager eyes into international directions. Iran is one such region that is vastly diversifying the contemporary art world, but perhaps unexpectedly: for the last 40 years, Iran has stood formidably closed off, from wars and sanctions that prevented its vibrant arts culture from permeating the western world.

The London outpost of Tehran’s CAMA Gallery (credit Ed Aked).

However, the unique Iranian modern style has begun its spread: Tehran’s cosmopolitan art scene has exploded, dotted with contemporary galleries. Tehran’s Contemporary And Modern Art Gallery (CAMA) recently opened branches in London, with developments in New York. In 2018, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art unveiled a blockbuster exhibition, In the Fields of Empty Days: The Intersection of Past and Present in Iranian Art, 125 works of art by 50 artists of media exploring the monarchy, cultural lore, and religious past in Iranian society. The Louvre Lens Museum’s summer exhibition The Rose Empire has helped open European awareness to Iranian artists. In a 2017 sale, Sotheby’s sold $1.6 million in Iranian art, with other auction houses like Bonhams and Christie’s selling over $15 million of the work of Iranian artists, against significant cultural odds placed before them.

Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, TMoCA, inaugurated by Empress Farah Pahlavi in 1977.

These sales come against many odds: Iranian legislation placing limitations on freedom of expression have present obstacles for Iranian artists, from censorship blocks to capital punishment for insults to Islam. In the aftermath of Iran’s 1975 revolution, perceptions of Iran as repressive, and its artists as constrained, permeated Western thought. For decades government sanctions prevented art movement into and out of the country. Gallerists, at the forefront of Iranian cultural outreach, could not show work with excessive nudity, sexual themes, and criticizing Islam or the government.

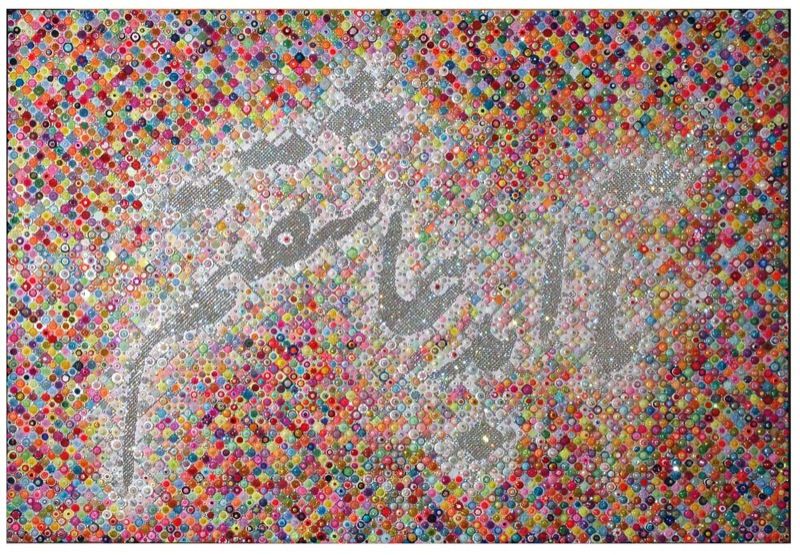

The work of A1one, pseudonym of artist Karan Reshad, who pioneered graffiti and street art in Iran.

And yet, Iran’s creative output cannot not be stifled. These restrictions on visual culture and art production have given birth to progressive art spaces, with artists producing work challenging global conceptions of Iran. To circumvent government censorship, Iranian artists have found creative subjects, subtle allegory, and references to traditional mysticism, to relay layered, cultural messaging. Exciting imagery, political parodies, and retellings of Iranian histories assert Iranian modernism in the face of Western stereotypes. Contemporary Iranian artists today pioneer arts scenes in Tehran and abroad, with firm groundings in Iran’s rich heritage and history, armed with contemporary experiences and disciplines.

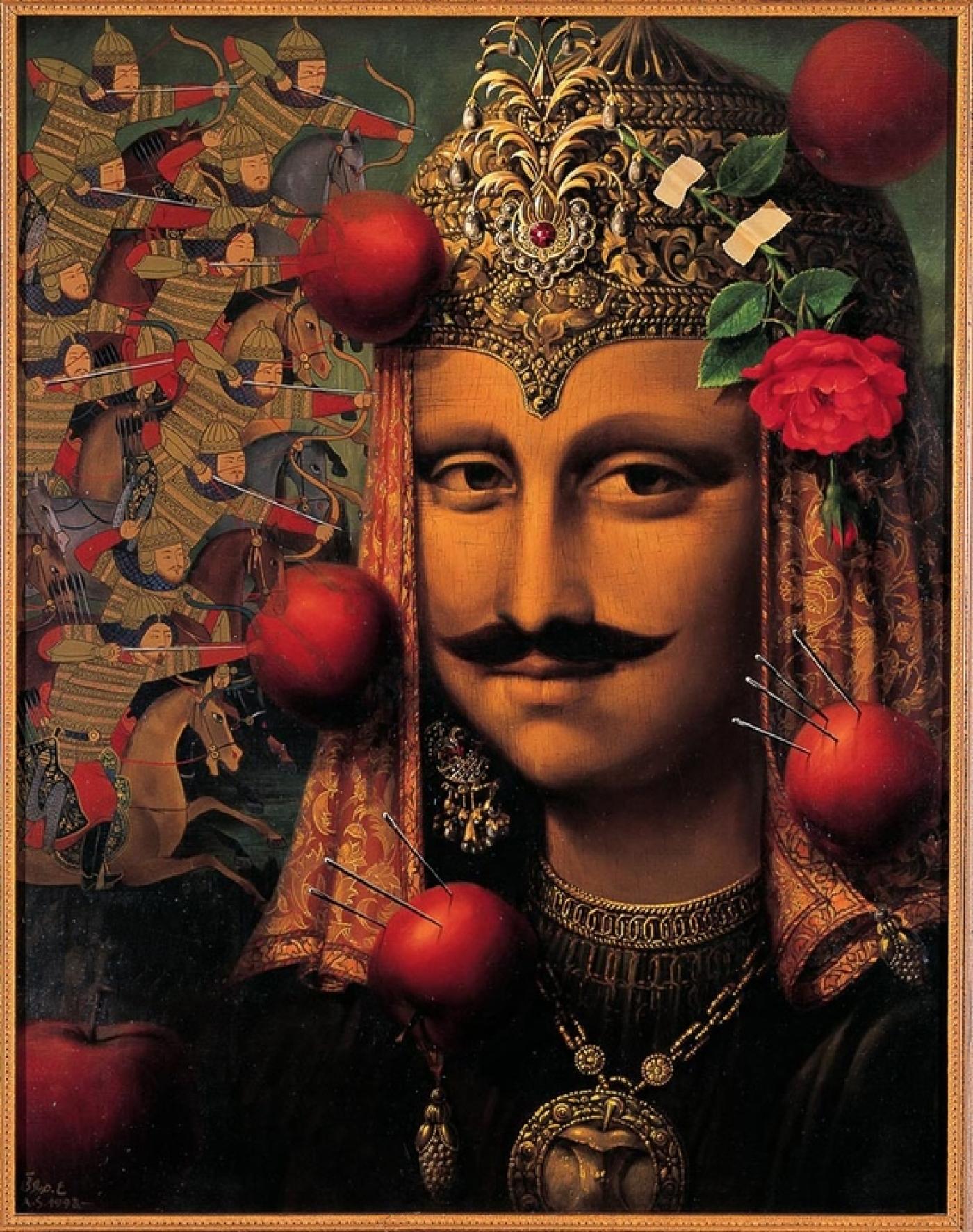

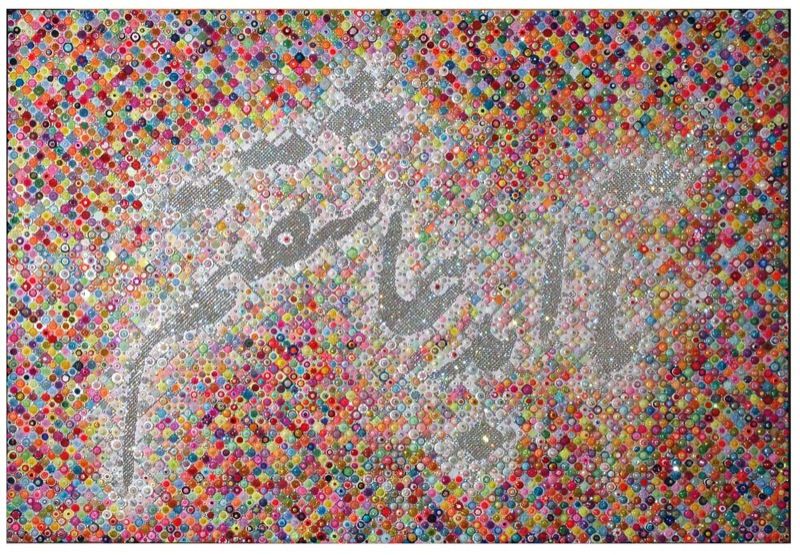

Farhad Moshiri, a mixed-media artist whose conceptual pop aesthetic and focus on consumer culture situate him at the cross-roads of the Middle East and the West.

Much of the present artistic flourishing can be traced back to Iran’s “Queen of Culture,” Her Imperial Majesty Empress Farah Pahlavi. Born of an affluent family, she became queen after marrying Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in 1959 at 21 years old. Having studied architecture in Paris and Switzerland, her mission as empress was unique and unprecedented: preserving Iranian tradition while endorsing art creation, building artistic infrastructure, developing Iranian education and culture.

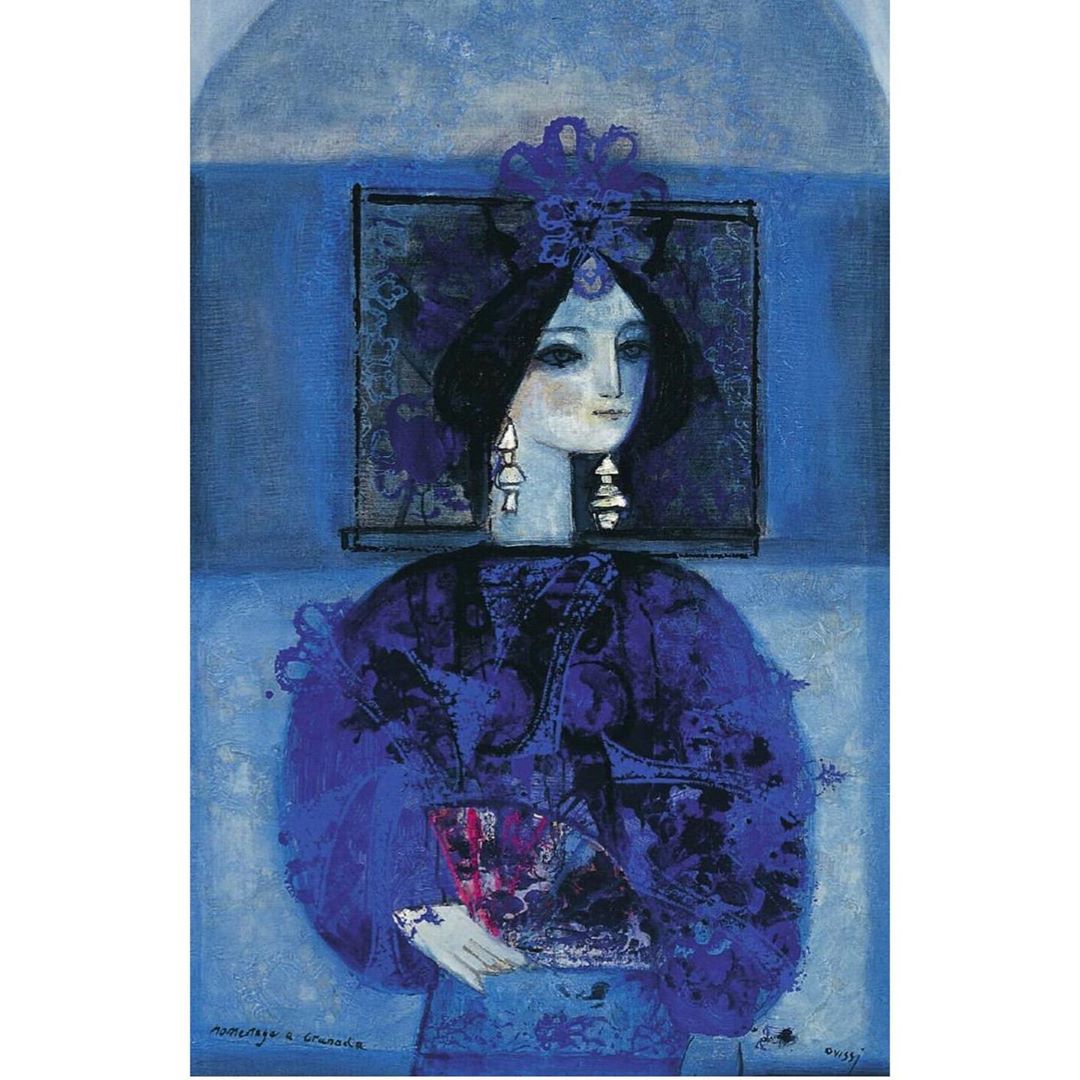

American-Iranian artist Nasser Ovissi is known for his stylized paintings of Iranian women and horses, as meditations on the beauty of life.

While visiting art showcases and exhibitions, the empress continually heeded calls for permanent art spaces for Iranian artists to display their work. She then commissioned the construction and acquisition of contemporary art for the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMoCA), a feat in direct conversation with the New York Guggenheim, speaking to Iran’s unique vantage point between the East and West. TMoCA served as a platform for Iranian art as well as bringing in Western masterpieces from Van Gogh, Rothko, Warhol, Picasso, and more. During her 20-year reign, the empress also helped to found the Negarestan Museum for Persian carpets, the City Theatre of Tehran, the Abguineh Museum, and the Museum of Reza Abbasi of pre- and post-Islamic objects. Thanks to her patronage and initiative, several other museums, gallery spaces, cultural centers, and national arts festivals illustrate the multidisciplinary artistic legacy of Iranian artists, from ceramics, textiles, metalwork architecture, calligraphy, and more. However, with the fall of the empire during the Islamic Revolution of 1979, her family came into exile, effectively ending such artistic revitalization projects in Iran. The TMoCA’s collection was shuttered into a safe.

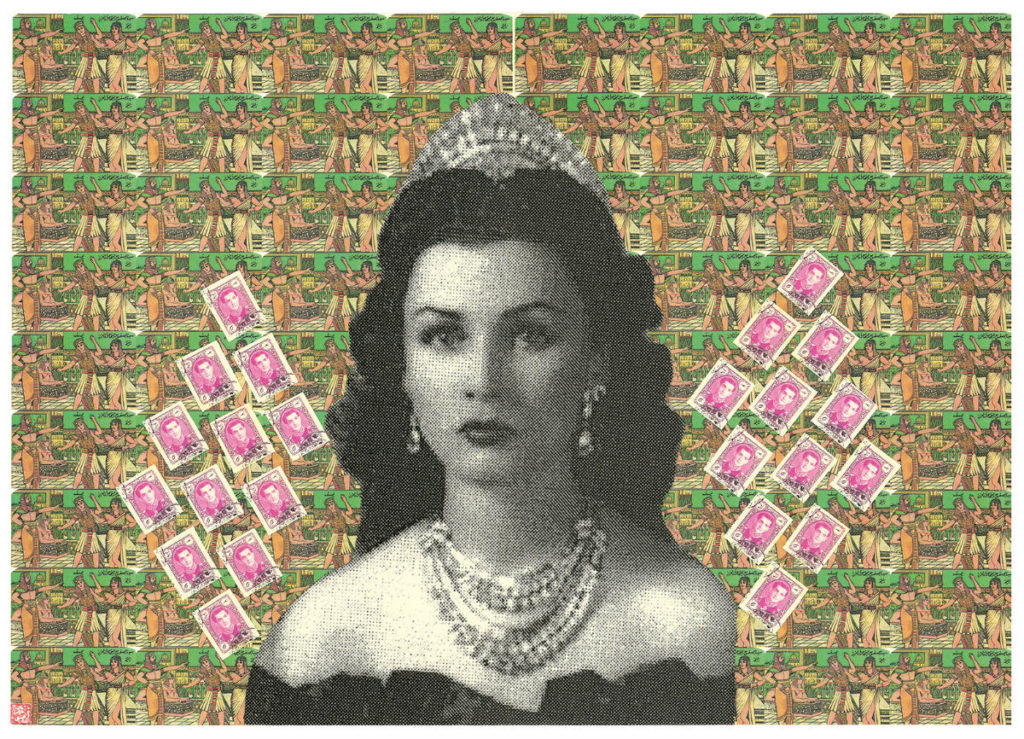

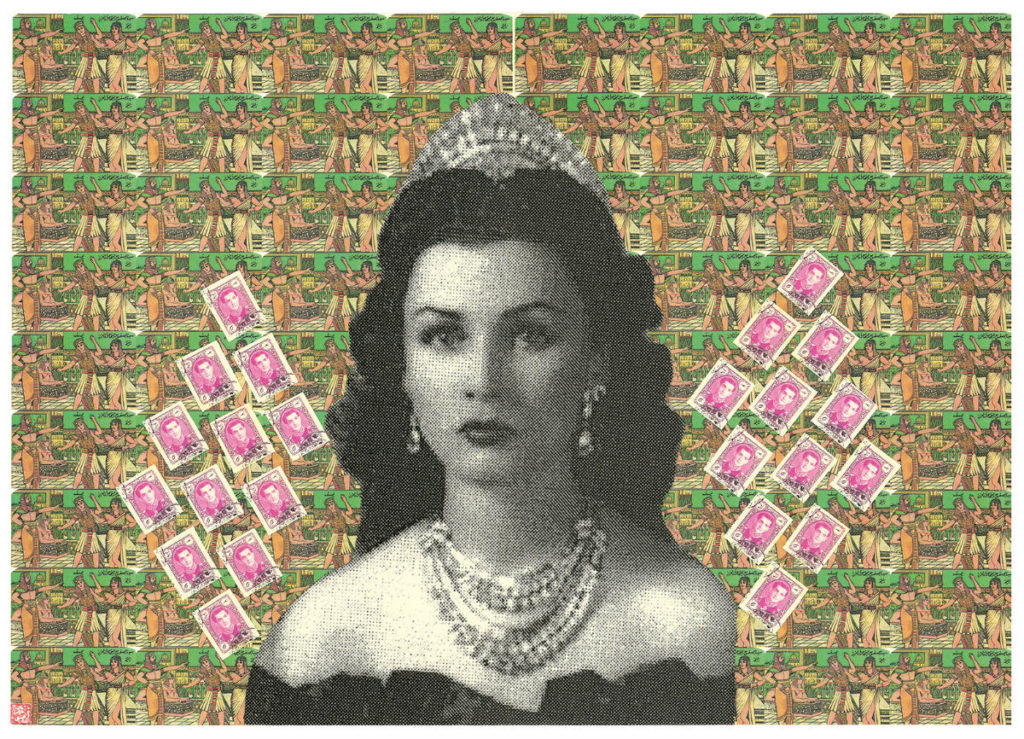

Afsoon, Shah and His Three Queens, from the series “Fairytale Icons” (2009). Printed paper collage on paper. Collection of Leila Taghinia-Milani Heller.

Optimistic Iranian artists and gallerists alike continue to observe positive changes in the arts markets. Recently-lifted government sanctions on the import of works has allowed art spaces to collaborate with international artists and receive their projects. Outstanding curatorial projects have resulted, like Ab-Anbar’s group exhibition, Mass Individualism: a Form of Multitude, showcasing the work of progressive Iranian artists investigating shifts in public and private space. Increased spending power and collector interest in young Iranians has stimulated global interests, and enticed visits from collectors and curators to Iran from around the world.

Tehran-based graphic design director Majid Abbasi, whose award-winning work has been published in international books, magazines, and international exhibitions.

Recent Trump administration U.S. sanctions on Iranian crude oil have threatened to destabilize the country’s budget. In the last year, the Iranian rial dropped in value about 70 percent against the U.S. dollar, followed by rising inflation as noted by the IMF. Since the early 2000s, Iran’s intellectual and artistic classes have gained international attention. Its collectors have sprung up interested in supporting younger contemporary artists. In spite of international and domestic obstacles, waves of bold Iranian artists and their gallerists continue to advocate for their country’s arts and culture internationally. We implore you to find Iran at the next Art Basel or Frieze: theirs is a presence that cannot be sanctioned.

Salman Khoshroo, Figure from the “Wanderer” exhibition,oil on canvas, 140x160cm.

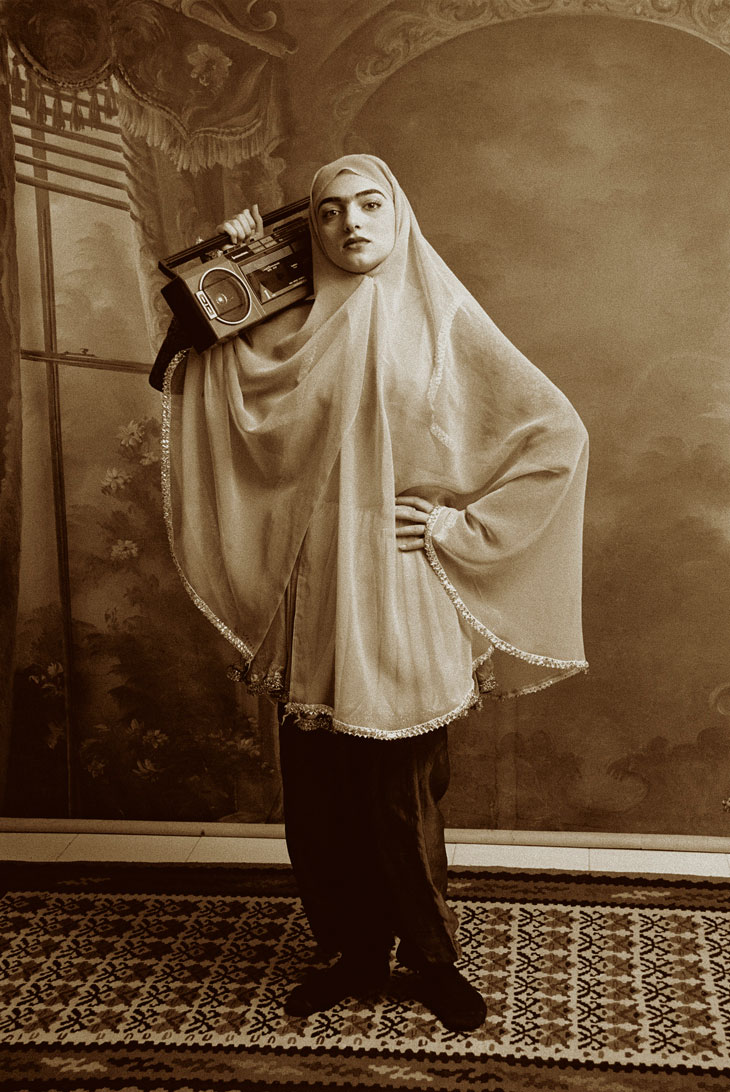

From Shadi Ghadirian’s Qajar series at the Saatchi Gallery, an acclaimed photoseries for its portrayals of Iranian women wearing Qajar-era clothing contrasted with objects of modernity.