In an age of typing and texting, the art of handwriting has seemingly fallen from grace. In the US, cursive handwriting is less and less a part of common-core standards and its utility has become an impressively polarizing topic. Handwriting and cursive are deeply tied to history: proponents of teaching cursive script argue that younger generations need it to be able to read historical documents, literary papers, archival collections––and even memorabilia so simple as a grandmother’s diary or their parents’ love letters.

Calligraphy itself is defined as the art of beautiful handwriting. The term may derive from the Greek words for “beauty” (kallos) and “to write” (graphein). In her book Calligraphy: From Calligraphy to Abstract Painting, French type designer Claude Mediavilla describes calligraphy as “the art of giving form to signs in an expressive, harmonious, and skillful manner.” In the Middle East and East Asia, calligraphy by long and exacting tradition is considered a major art, equal to sculpture or painting, though nearly every global culture possesses a rich calligraphic tradition.

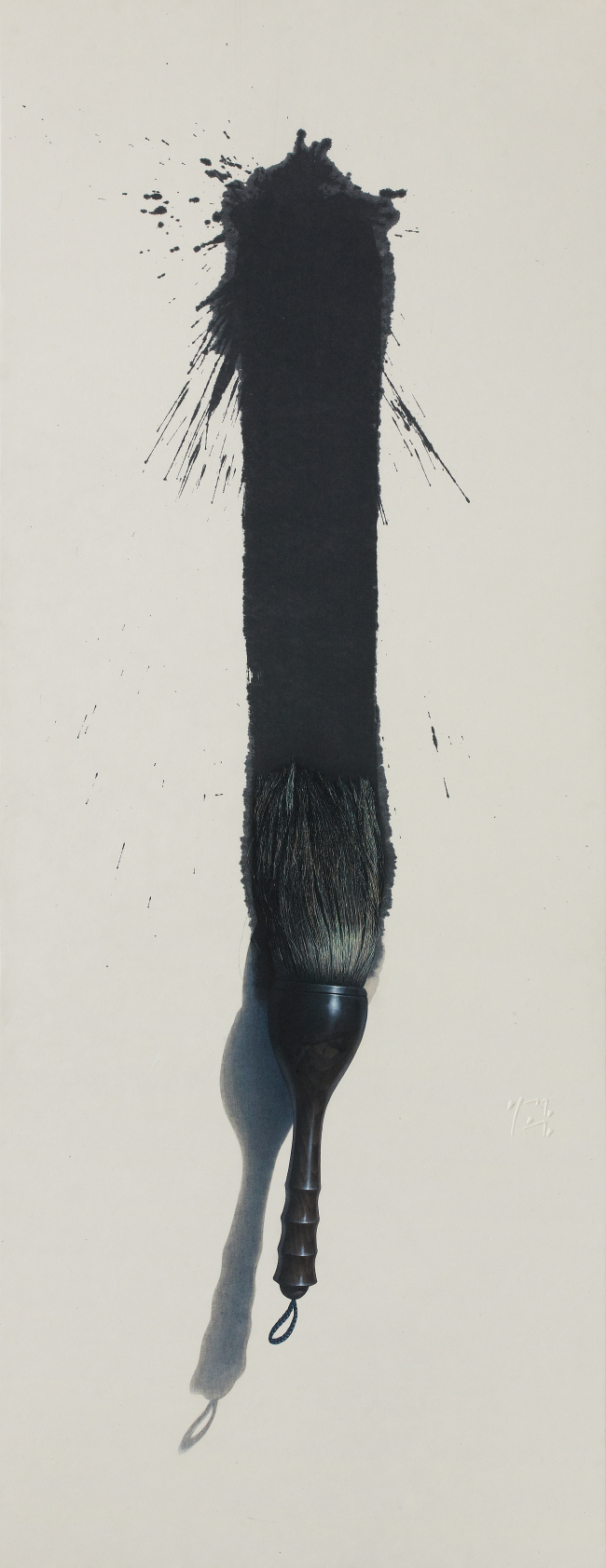

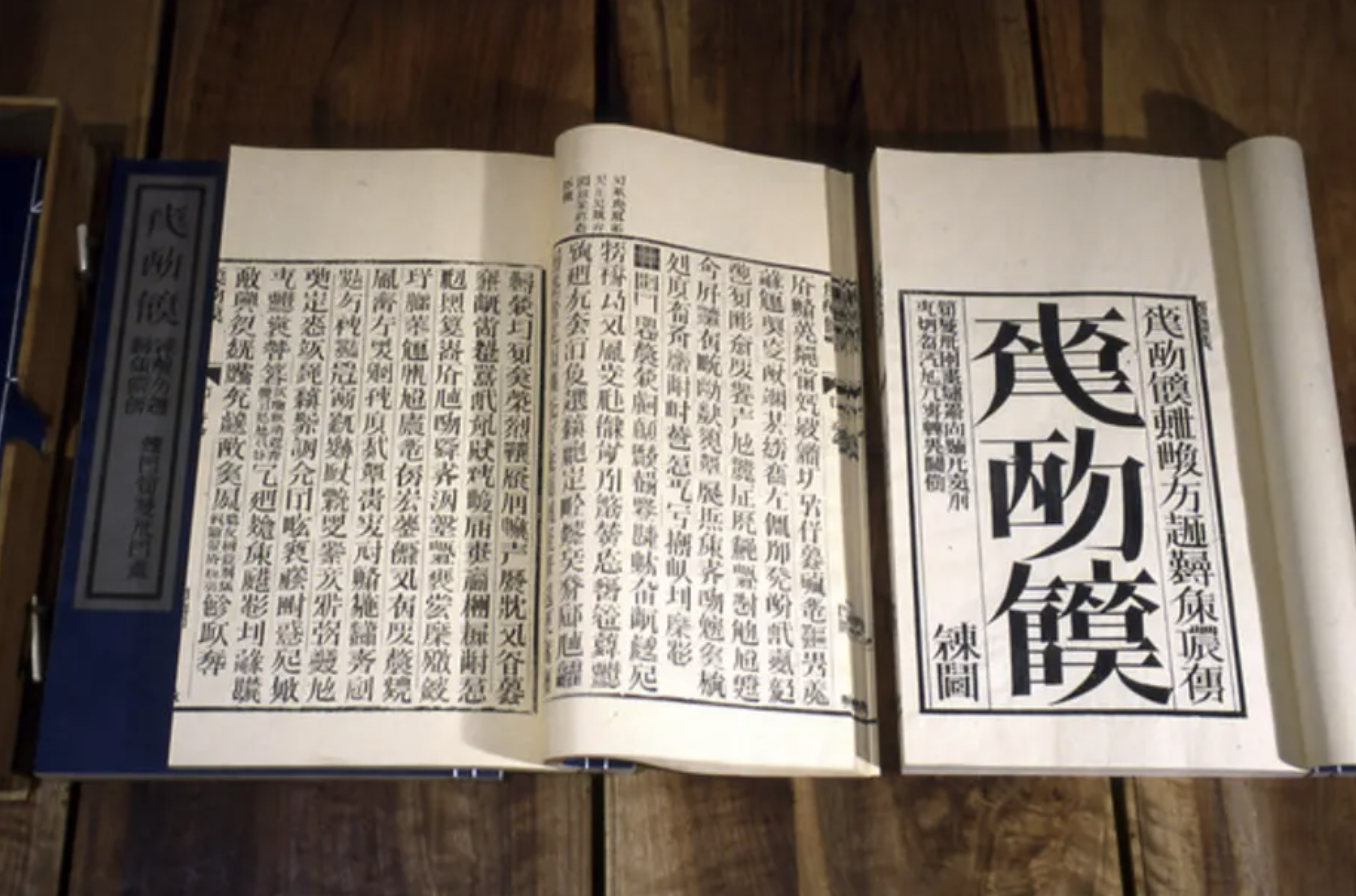

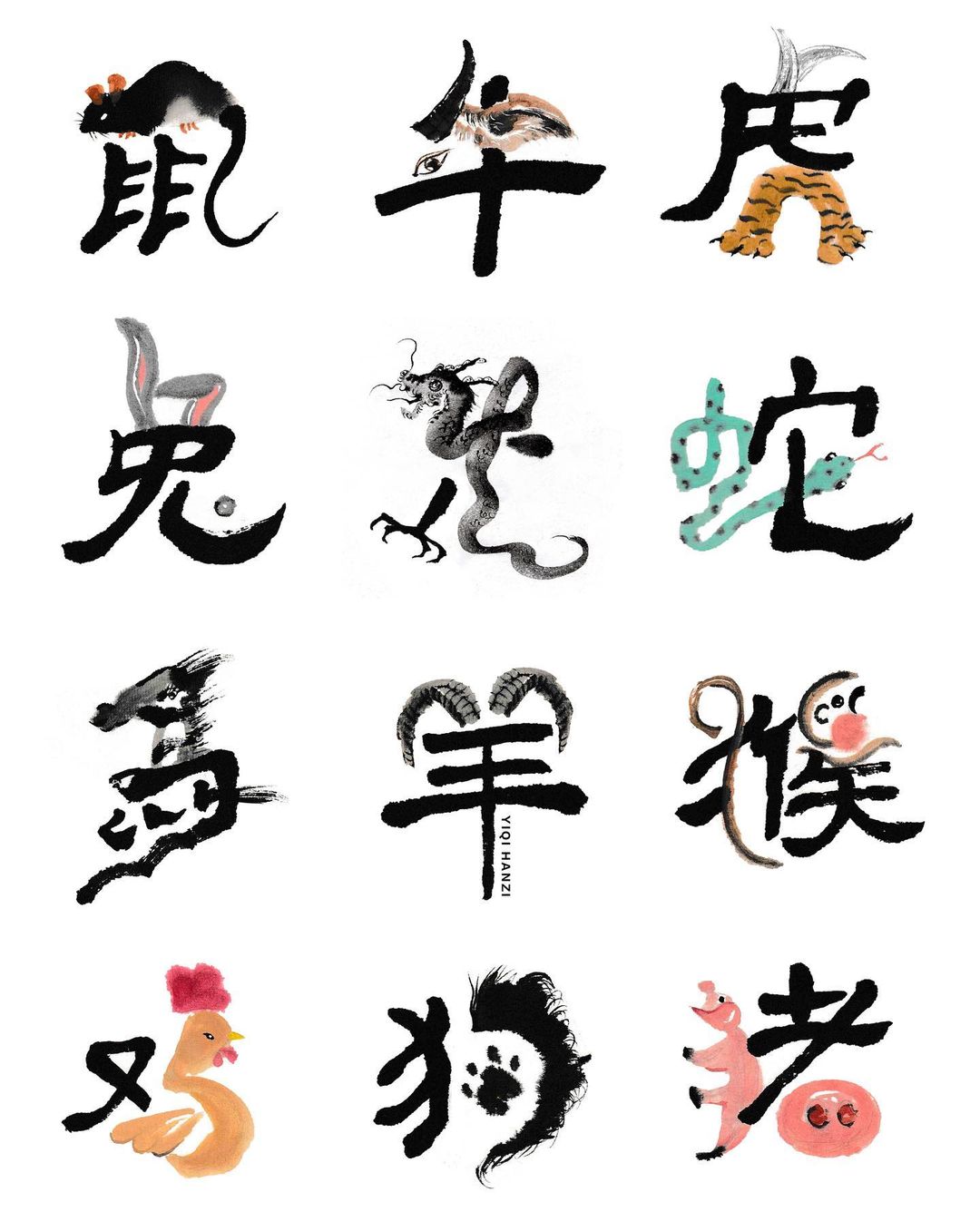

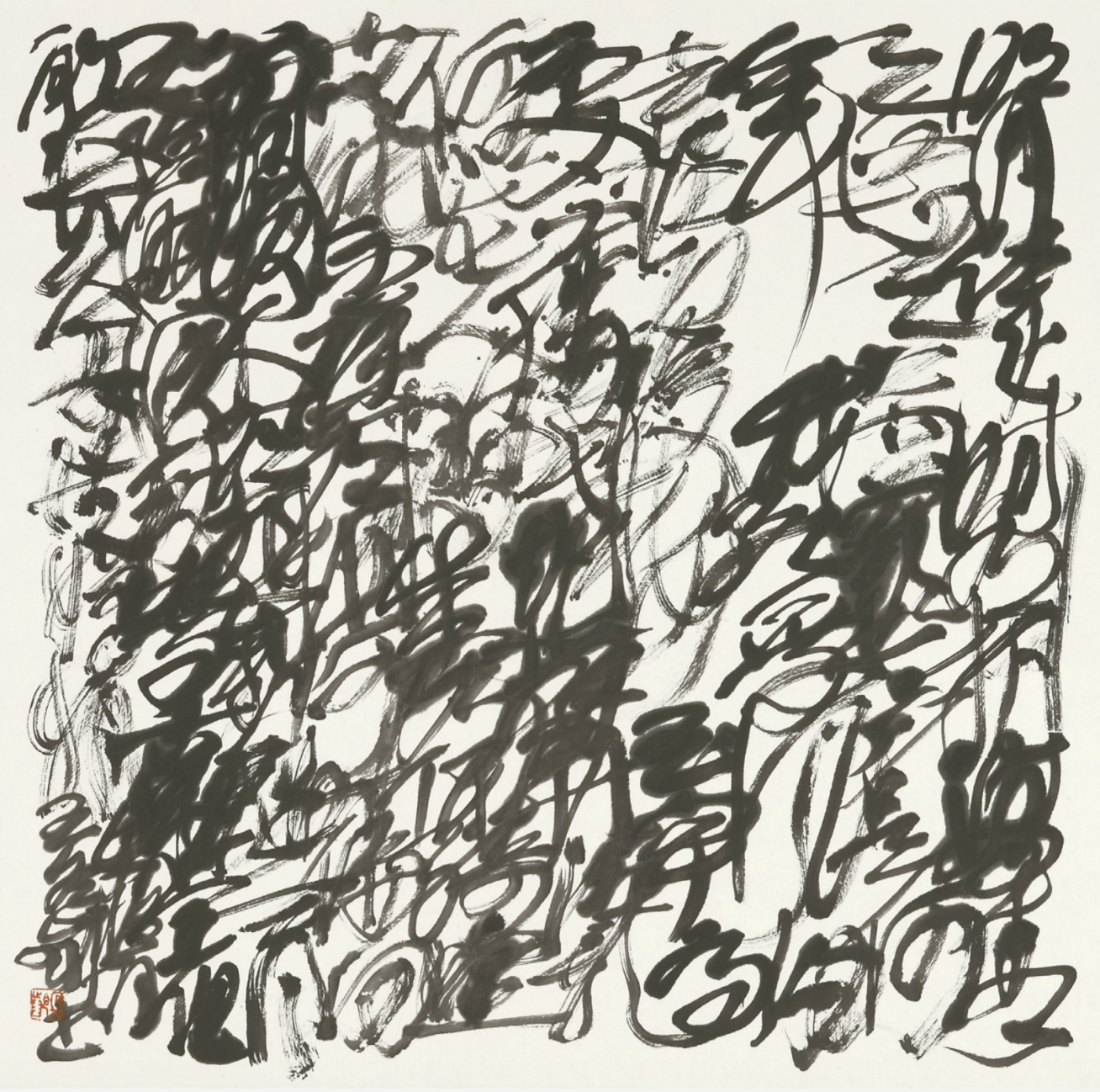

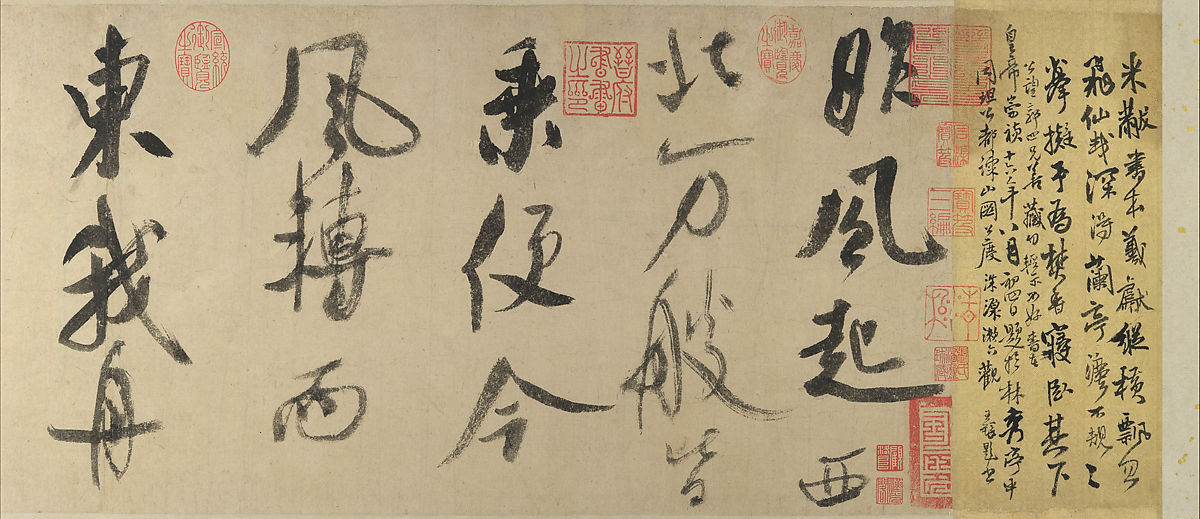

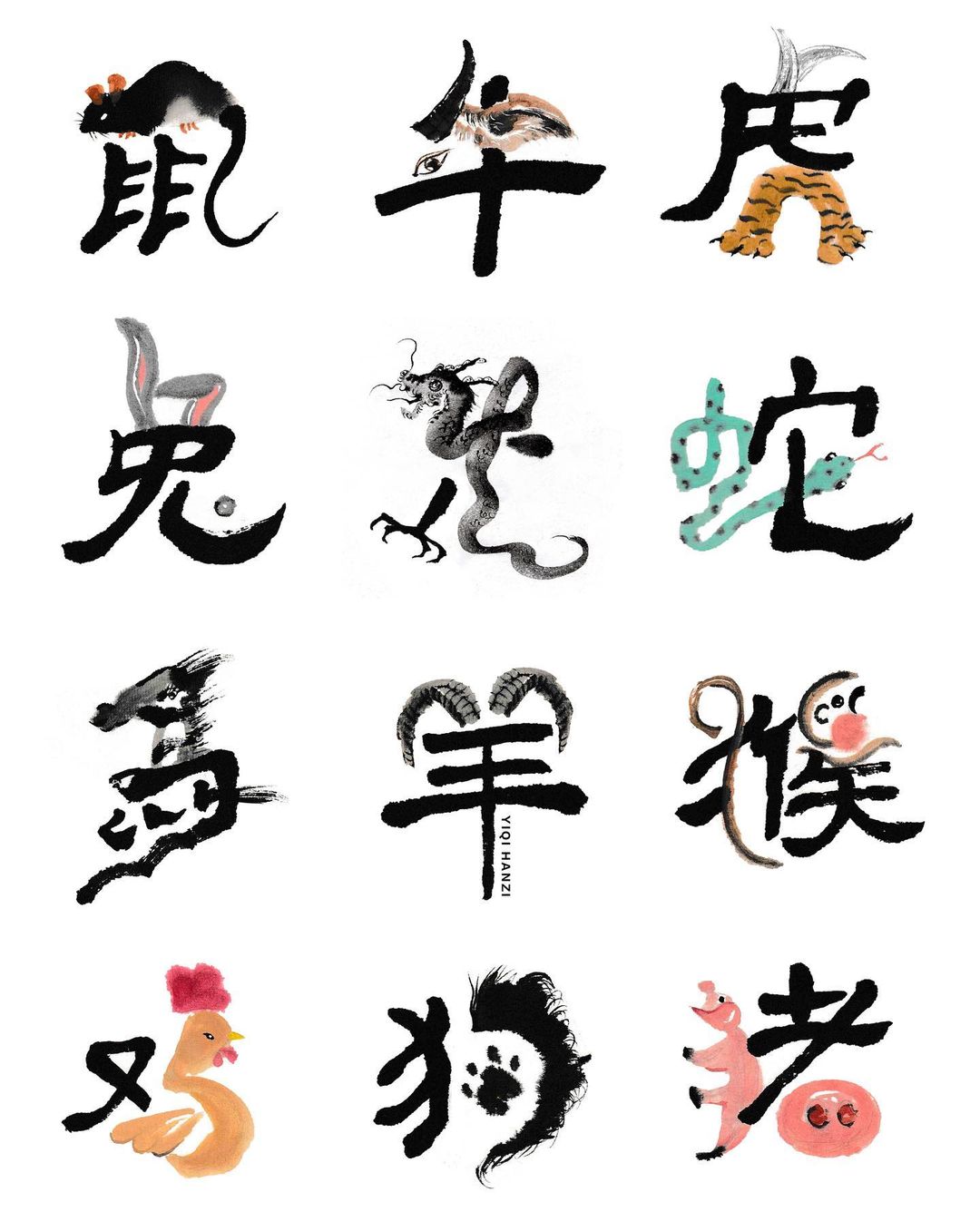

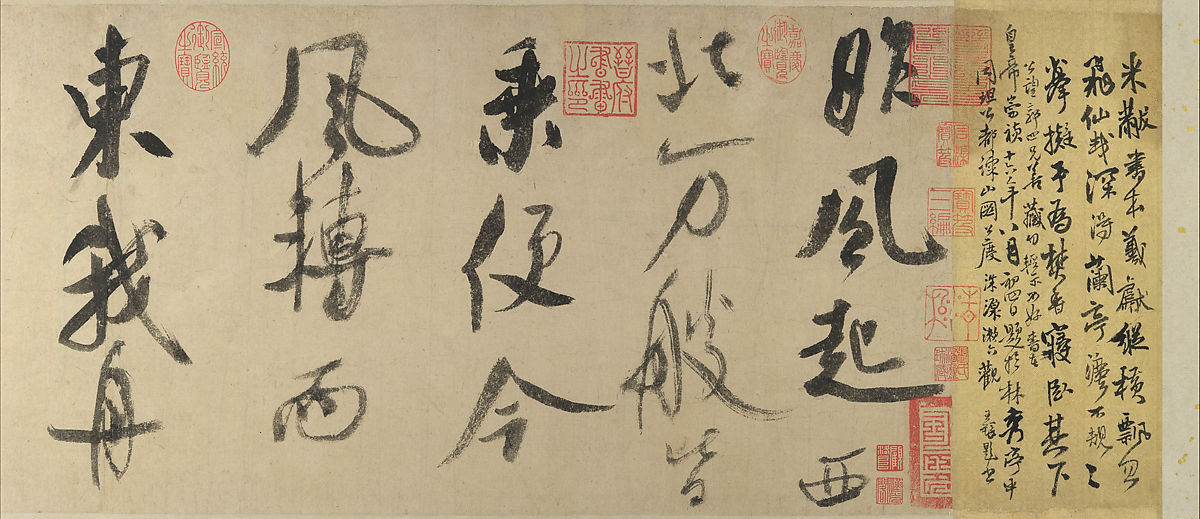

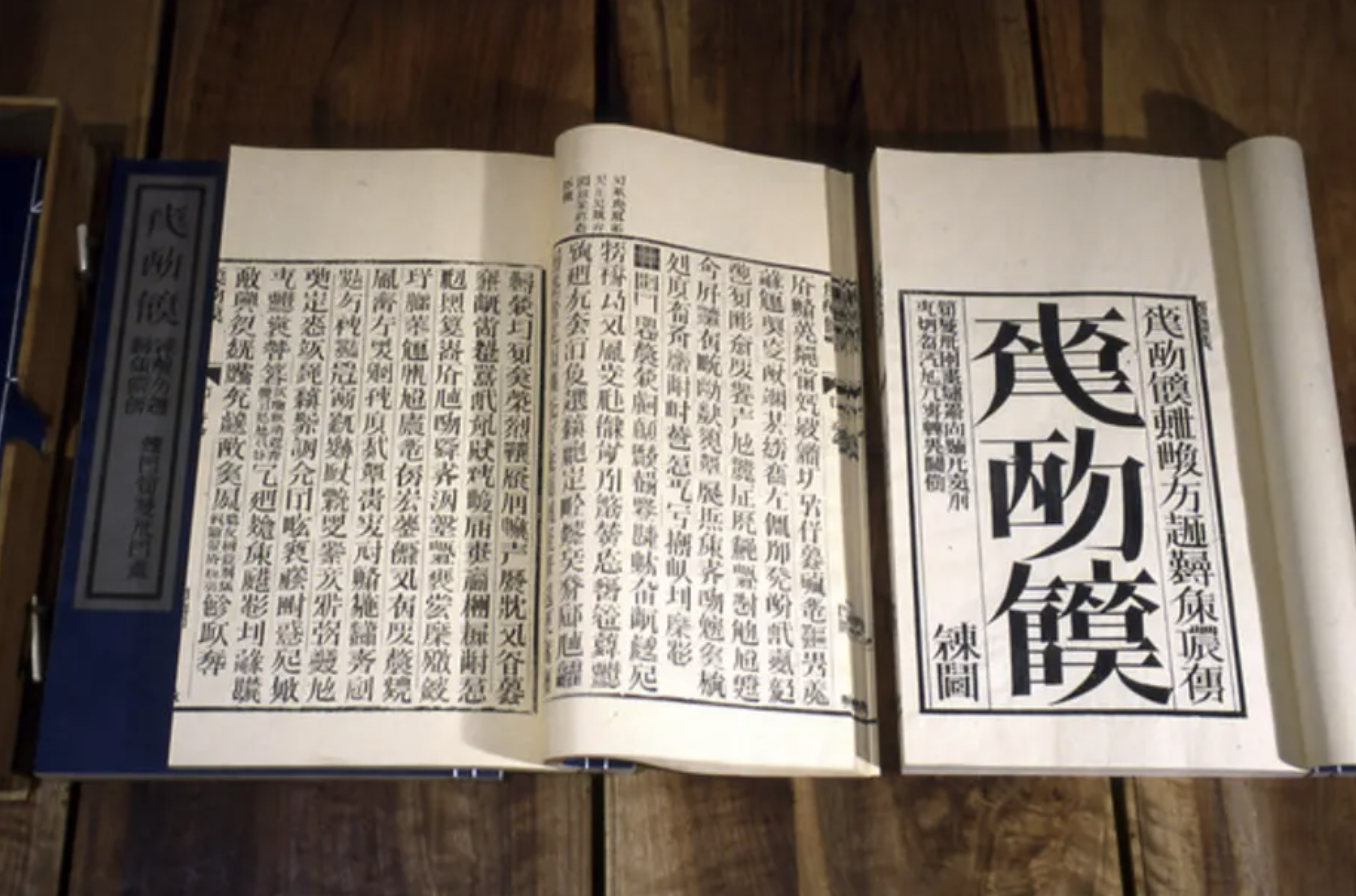

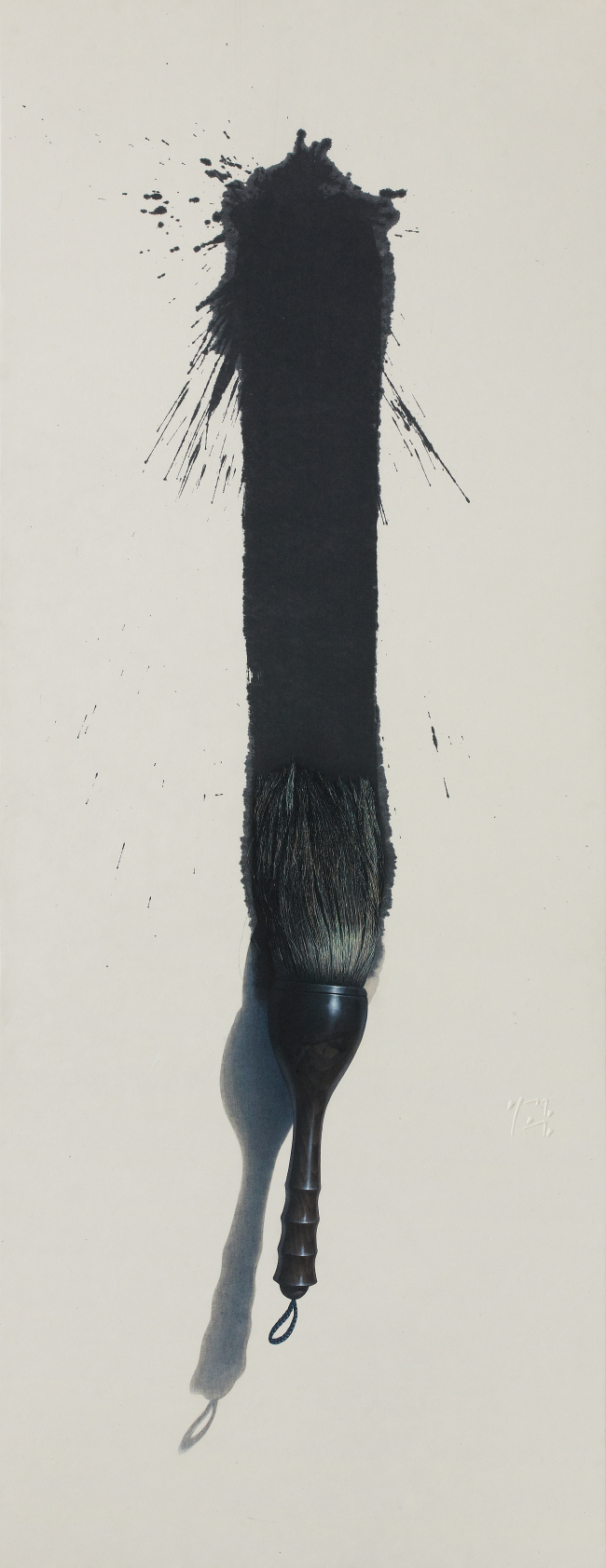

In pre-modern China from the fourth century CE, calligraphy was the paramount visual art and it flourished as one of the oldest global calligraphic traditions. Literati scholars in China and Japan cultivated skills in poetry, calligraphy, and paintings to express their personal feelings rather than demonstrate professional skill. The rhythm, movement, and flow of traditional characters was highly prized by the intelligentsia, Collectors and connoisseurs, who saw exceptional calligraphy as an extension of good character or upright morality. Highly-skilled brushwork continues to be a valued skill and art form, enduring from dynastic times, still following prescribed strokes but in an array of script styles highly personal to the calligrapher. Ranging from clearly defined to wildly expressive, Chinese calligraphic scripts range in styles from seal, clerical, regular, running, and cursive. The seal, clerical, and regular scripts are executed with clearly defined strokes, making them highly legible and orderly. Running and cursive scripts, on the other hand, are defined by fast, gestural, spontaneous strokes with characters flowing into each other continuously.

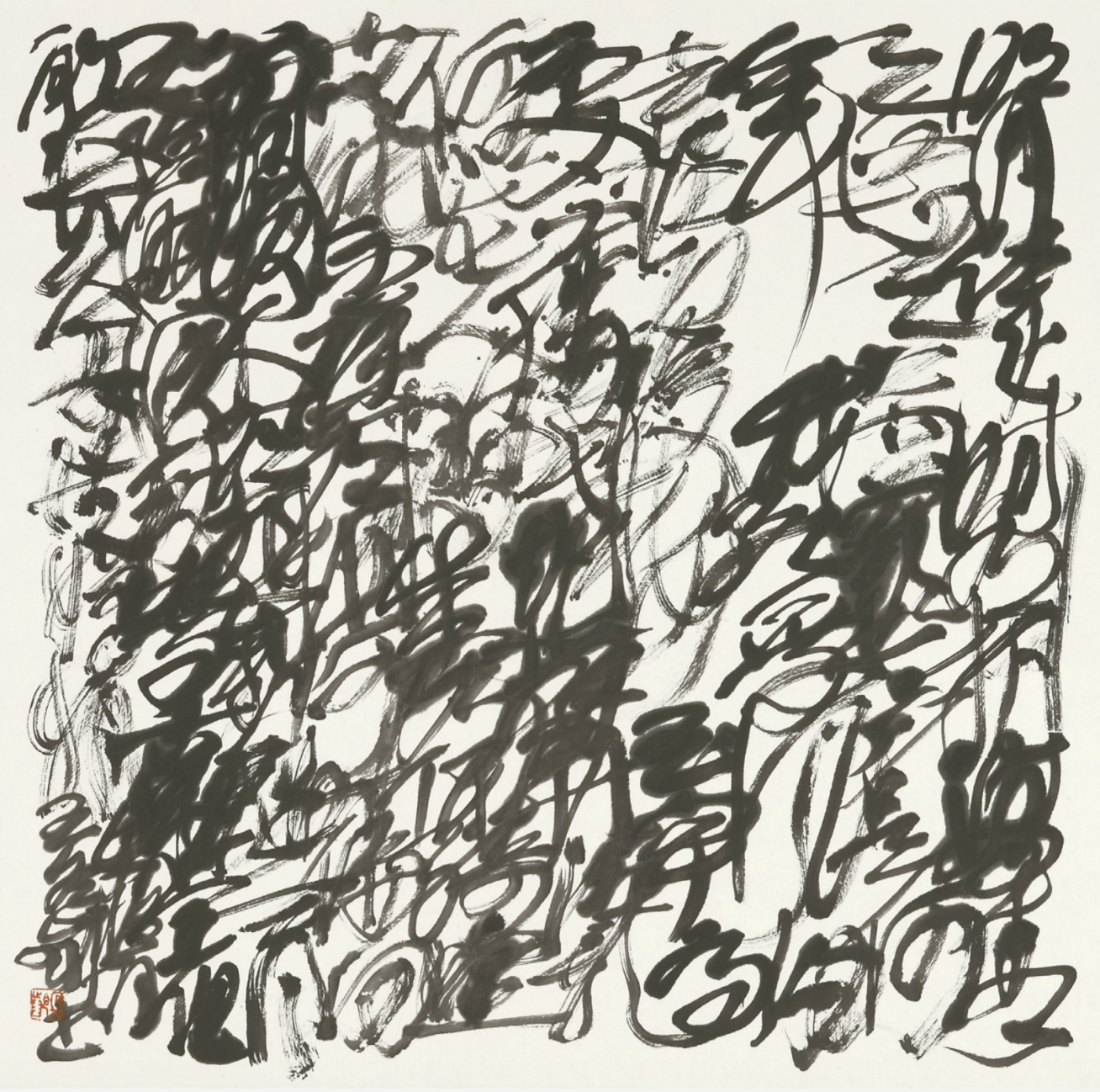

Though literacy of Chinese characters is key to being able to produce calligraphic work, it is far from necessary to appreciate the art form. The beauty of the medium, for all its sweeping freedom and poetic poise, trumps any literal messaging. The art form also continues to involve, in dialogue with a more globalized world. Celebrated contemporary Chinese artist Xu Bing’s installation Book from the Sky is regarded today as one of the masterpieces of twentieth-century Chinese art. The 1,500 square foot artwork transforms its display space with an immersive temple-like collection of books, hanging scrolls, and wall panels inscribed with text, seeming to promise ancient wisdom and legibility. However, these calligraphic works are comprised of 4,000 pseudo-Chinese characters devised by Xu himself, carrying no meaning. Instead, they are abstracted forms reflecting on the history of calligraphy and literacy, trumping the viewer. The work of contemporary calligraphers themselves, such as Wang Dongling, can be read in direct dialogue with Euro-American artists, such as the action paintings of Jackson Pollock. Japanese artist Saburo Hasegawa spent many years of his life in San Francisco, collaborating with Beatnik poets and Zen practitioners Gary Snyder and Alan Watts, teaching drawing at the California College of the Arts and believing that only in the United States could he create fully abstract art influenced by Japanese calligraphy traditions, called shodō (書道). Hasegawa called calligraphy “a great treasure house for abstract painting.”

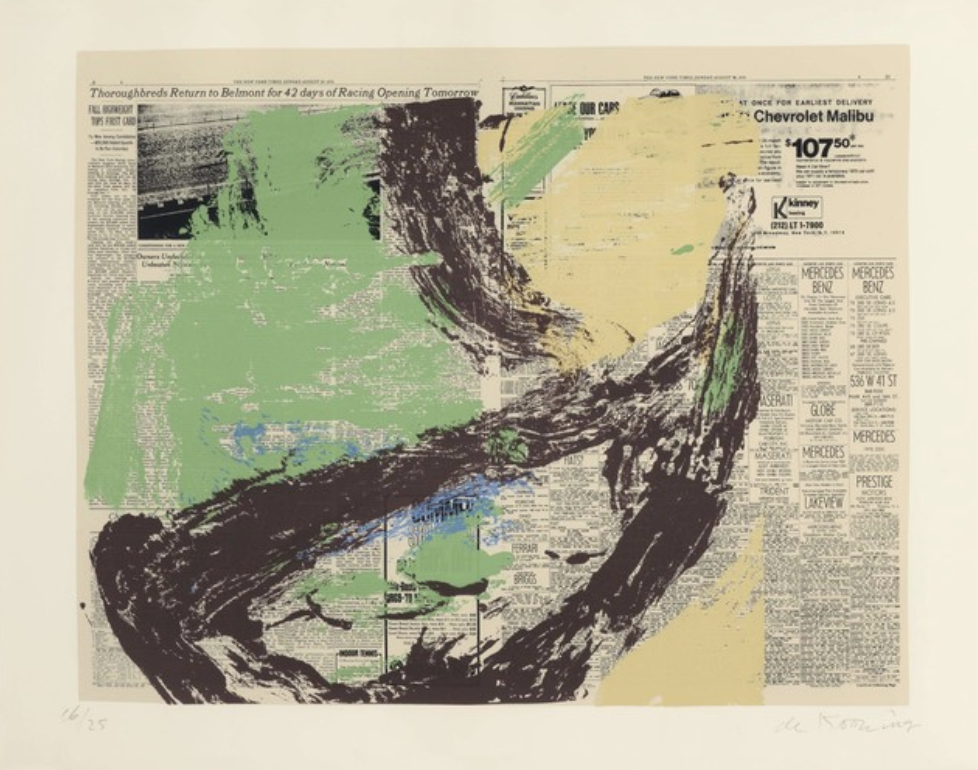

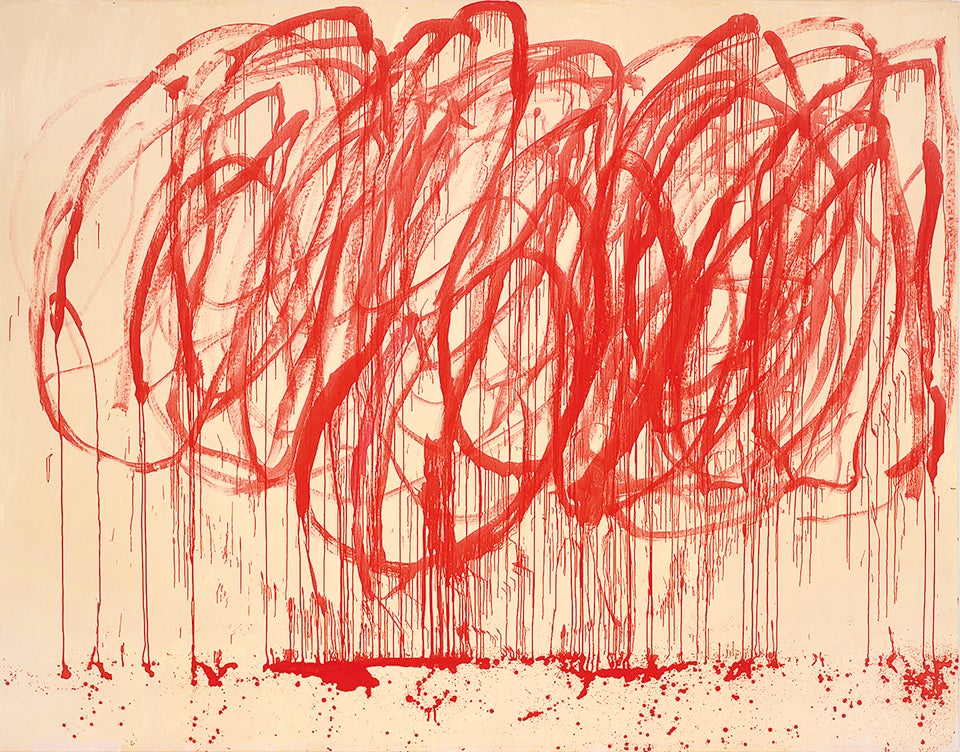

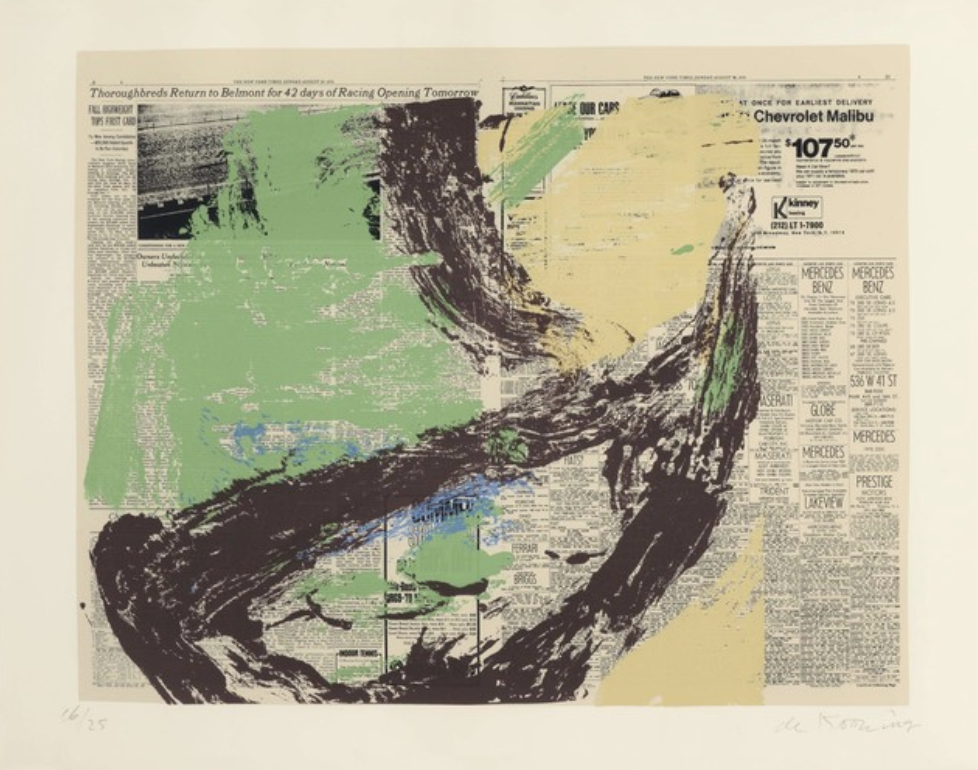

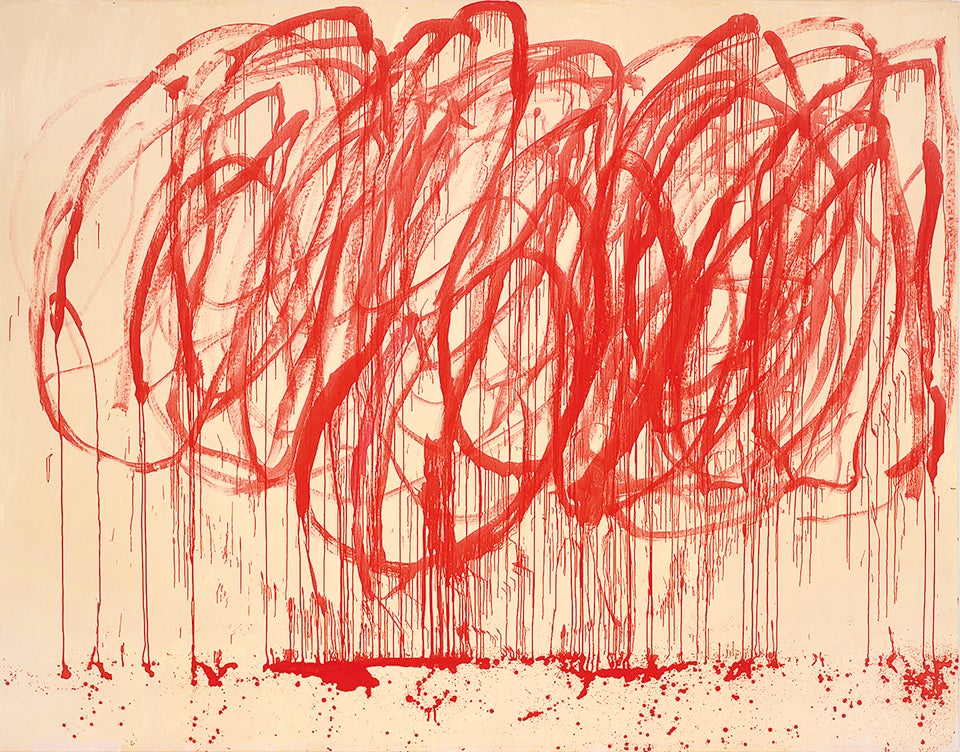

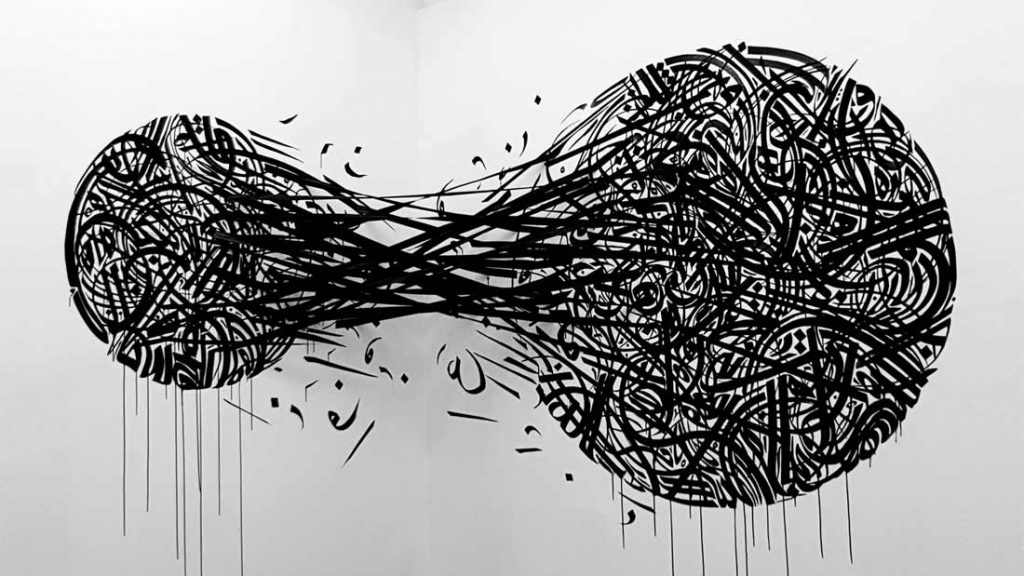

In the 20th century Western world, a calligraphic revival in Great Britain reacted artistically against the mechanization of manual crafts. And the greatest painters at the height of abstraction cited calligraphic traditions as inspiration, leaning heavily on the communicative power of gesture and line to convey meaning. Following the cultural shifts of World War II, the idea of forming a deeper connection with the interior self was of monumental concern for many artists. The Abstract Expressionists in particular were chiefly interested in historic philosophies or traditions that could give way to new modes of artistic expression that were deeper, more intuitive, and more honest. American abstraction sought to no longer relate to figurative subject matter, instead harnessing markings and gestures as emotive forces in themselves––much in the same way calligraphy elevates the written word beyond merely communicating fixed thoughts. Indeed, both forms of expression find their origin points in the movement of the body. Many of the Western world’s fathers of abstraction, from Jackson Pollock, to Wassily Kandinsky, to Cy Twombly, to Willem de Kooning, were deeply influenced by the calligraphic spirit. Indeed, from calligraphy’s foundation in written language, the calligrapher could depart from symbol and meaning to convey metaphysical truths, the artist’s implement acting as an extension of the body and spirit. The great Abstract Expressionists sought this same intuitive, bodily expression in their work, highly motivated by Eastern calligraphic traditions.

The American painter Franz Kline in particular is known for his monumental black-and-white paintings that treat the medium of oil with a distinctly calligraphic freedom. Kline employed white canvases and aggressively energetic black brushstrokes to explore gestural movement and emotive transfer. Working on large canvases, Kline painted monumental markings that appeared to be quickly produced, but were the result of a long, deliberate process. His ability to convey the energetic slash of a calligraphic mark remains one of the most stunning accomplishments of his oeuvre. Jackson Pollock, too, went through a phase of experimentation with Japanese paper and India ink. He created a resulting series of black-and-white paintings whose references to East Asian script are a radical reevaluation of artistic process. Calligraphic expressions inspired Cy Twombly to create his signature freely-scribbled drawings, while de Kooning is considered to have mastered freely drawn lines in works such as Untitled (1975). Saburo Hasegawa was taken by the free-flowing forms of Western abstraction and introduced works by Kline, Motherwell and other abstractionists to artists in Japan, strengthening an inter-continental artistic dialogue founded in the calligraphic arts.

Several exhibitions have dedicated their curatorial premise on these connections between Western contemporary art and the expressive elements of traditional calligraphy. The Seoul Art Calligraphy Museum holds exhibitions featuring artworks that highlight the art of handwriting and creating collections of paintings that explore handwriting. Its 2013 exhibition, At the Nexus of Painting and Writing, in collaboration with The Written Art Foundation, featured 79 works by 59 international artists whose works highlight the importance of the physical human touch in the digital age, and the influence of calligraphy on contemporary art, from Lee Jung-woong to Shirin Neshat.

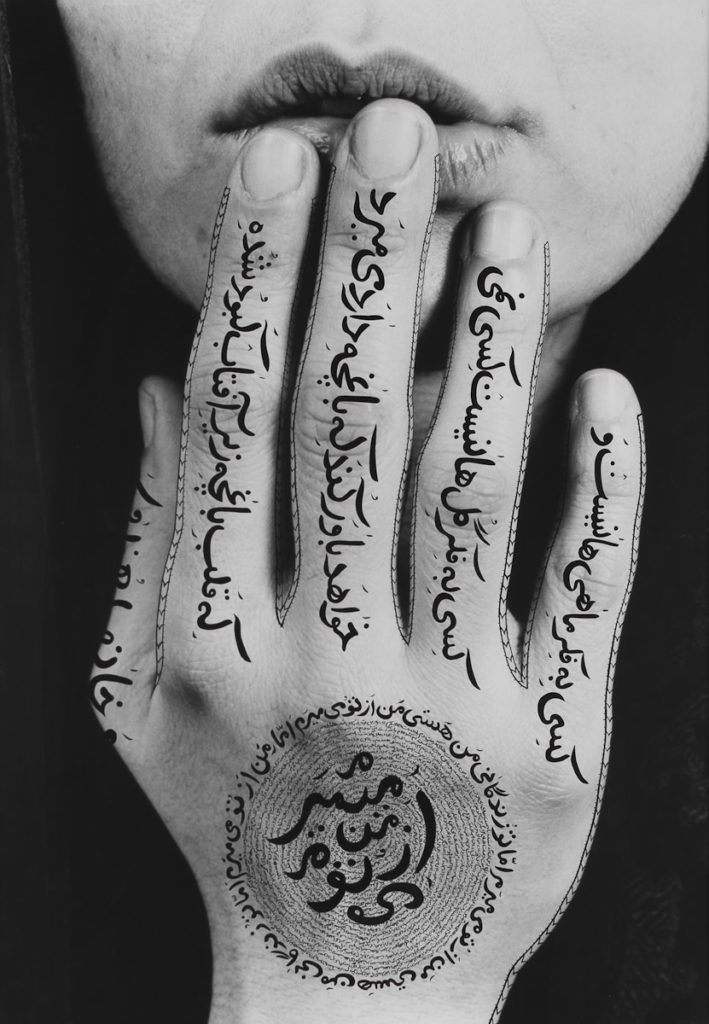

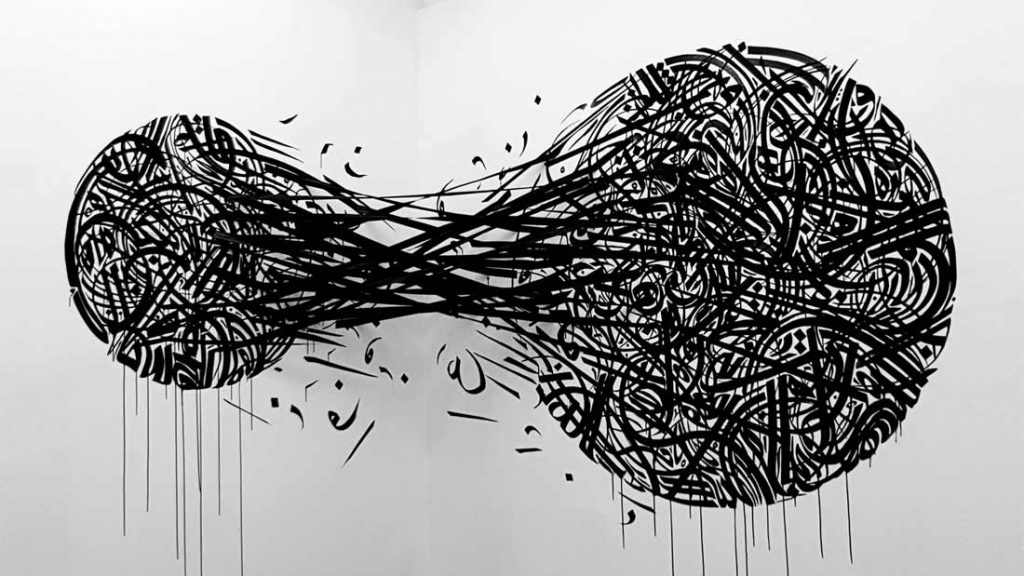

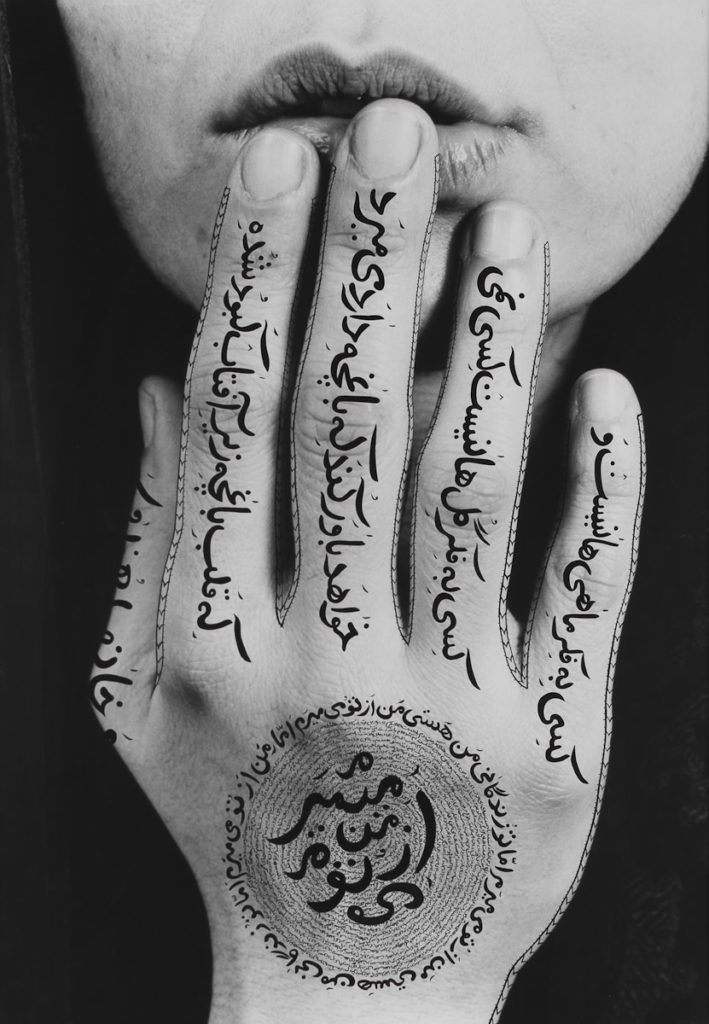

As one of the most stunning artistic careers in the field of photography, video and film today with a penchant for Persian calligraphy, Shirin Neshat’s US survey just this year was long overdue. From October 2019 to February 2020, The Broad Museum in Los Angeles presented a momentous exhibition Shirin Neshat: I Will Greet the Sun Again, the largest show to date of the internationally acclaimed artist’s approximately 30-year career. The show takes its title from a poem by Iranian poet Forugh Farrokhzad, the country’s first female poet to be publicly recognized and considered one of the bravest and transgressive writers in Iran’s new 20th century literature. The exhibition offers a rare glimpse into the evolution of Neshat’s artistic journey as she explores topics of freedom, individuality, societal oppression, the pain of exile, and the power of the erotic, pulling from turbulent events of recent Iranian history, including the Green Movement in Iran and the Arab Spring in Egypt. The poetic allure of Neshat’s photographs is partially owed to her use of Persian calligraphy, which stands historically as one of the most revered arts throughout the history of Iran. Many of Neshat’s photographs feature enchanting overlaid calligraphy: in the series Women of Allah, these calligraphed verses are lines by Forough Farrokhzad herself. Other writings are religious quotes from the Koran, or even cultural sayings that Neshat encountered throughout her upbringing. The calligraphic inscriptions wrapping around the forms of Neshat’s photographs are done in her own handwriting, and thus do not follow the strict dictates of Islamic calligraphy.

“I’m very interested in literature and poetic language because I’m very Iranian and in our culture, that’s how we deal with the word,” Neshat stated in an interview for the exhibition. “Poetry for a lot of us is a form of philosophy, it’s like living in our imagination. Much of the concepts and narratives are about my own life and issues I like to frame. The poetic language is introduced as a way to shape it, express the narrative. Every work whether it’s photographic or video, there’s always this element of poetry, allegory, and it’s for sure because I’m very Iranian.” She attributes her use of calligraphy, and the exotic Farsi characters, as the source of much of her work’s power.

The poetry, placed in sharp contrast to the straightforward portrait shot, suggests a depth and feeling that often goes unnoticed in Neshat’s subjects, particularly Iranian women: desires and ambitions, moving between intense private thoughts and emotions, and public political involvement in Iran.

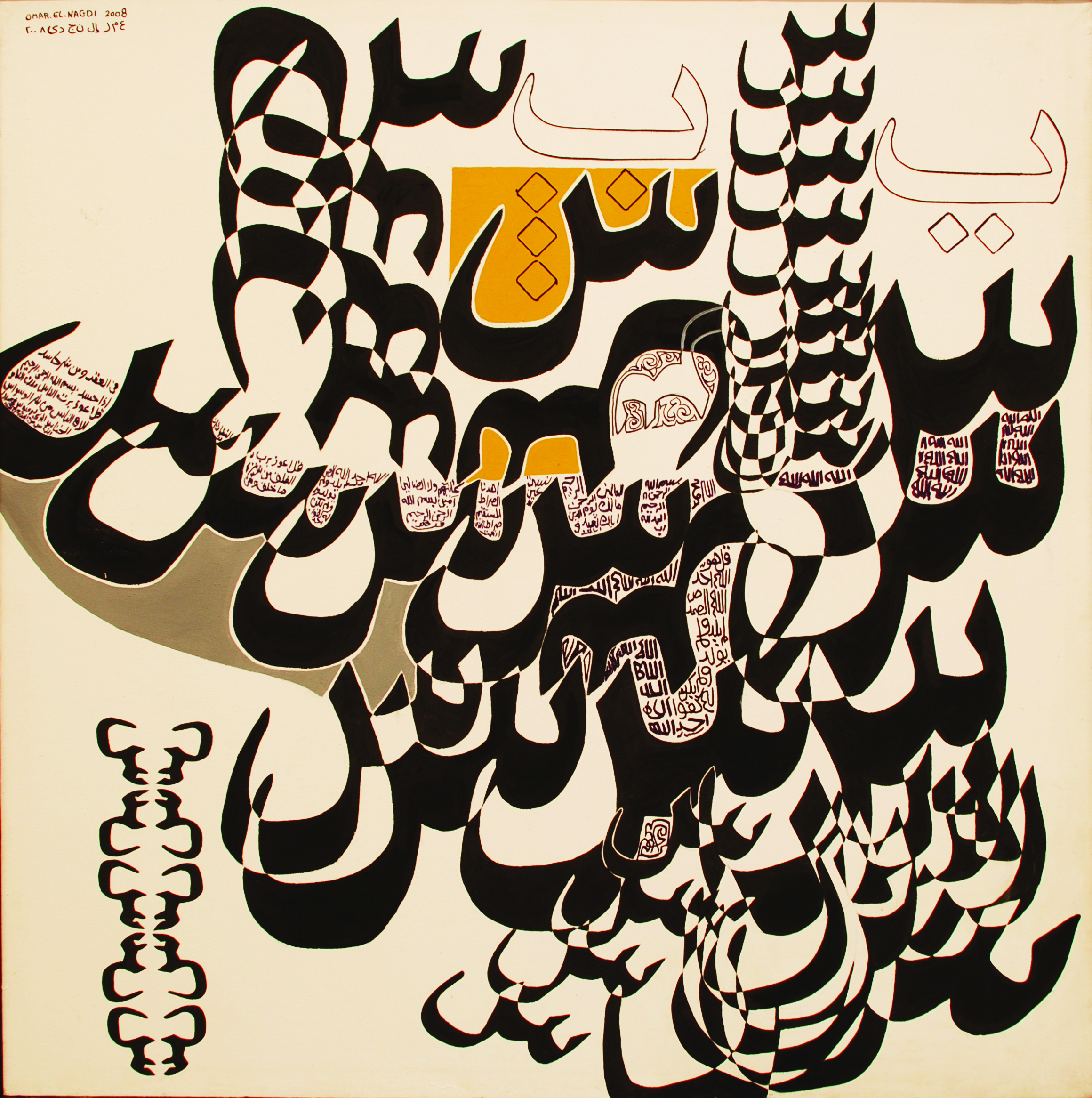

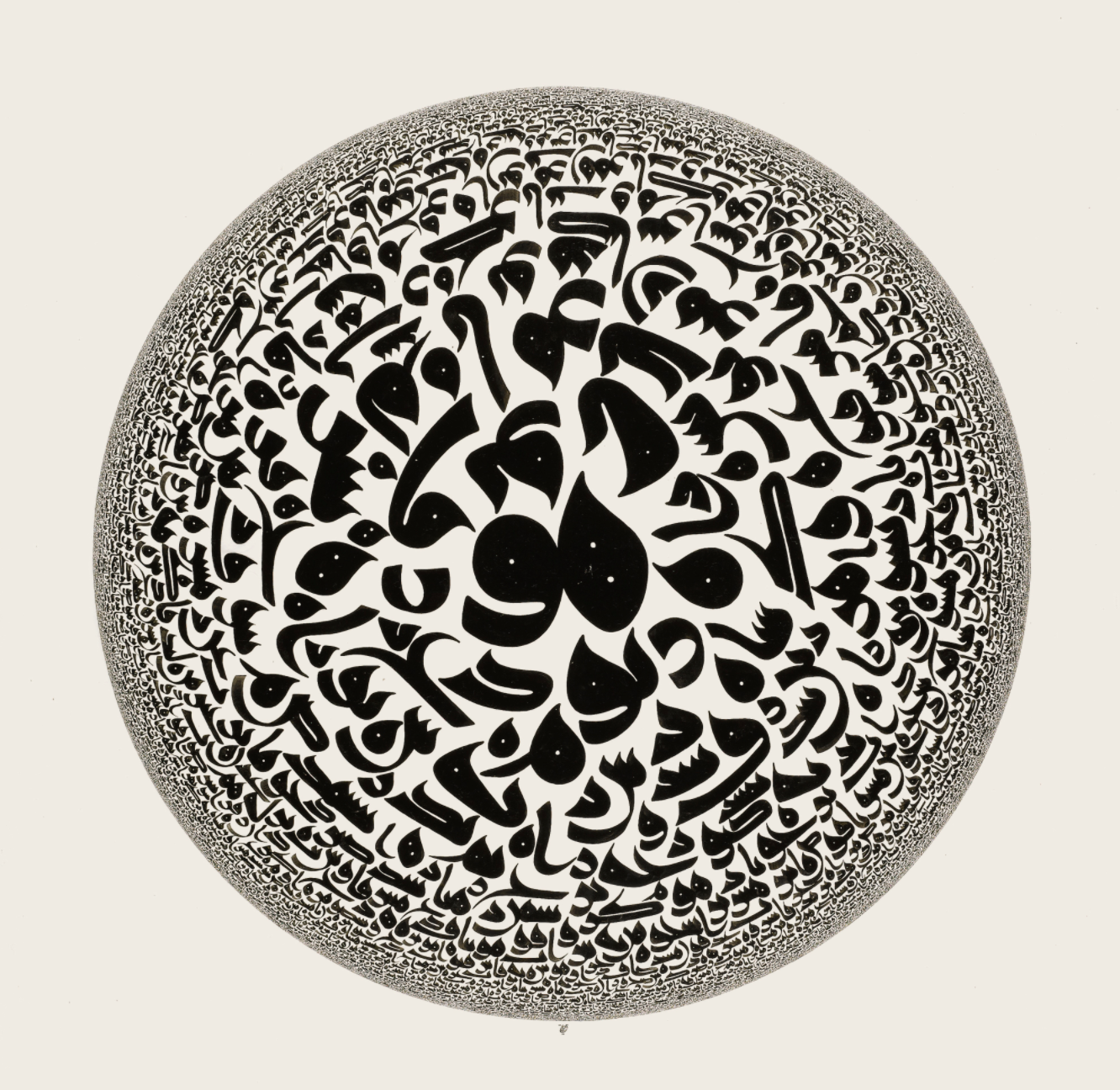

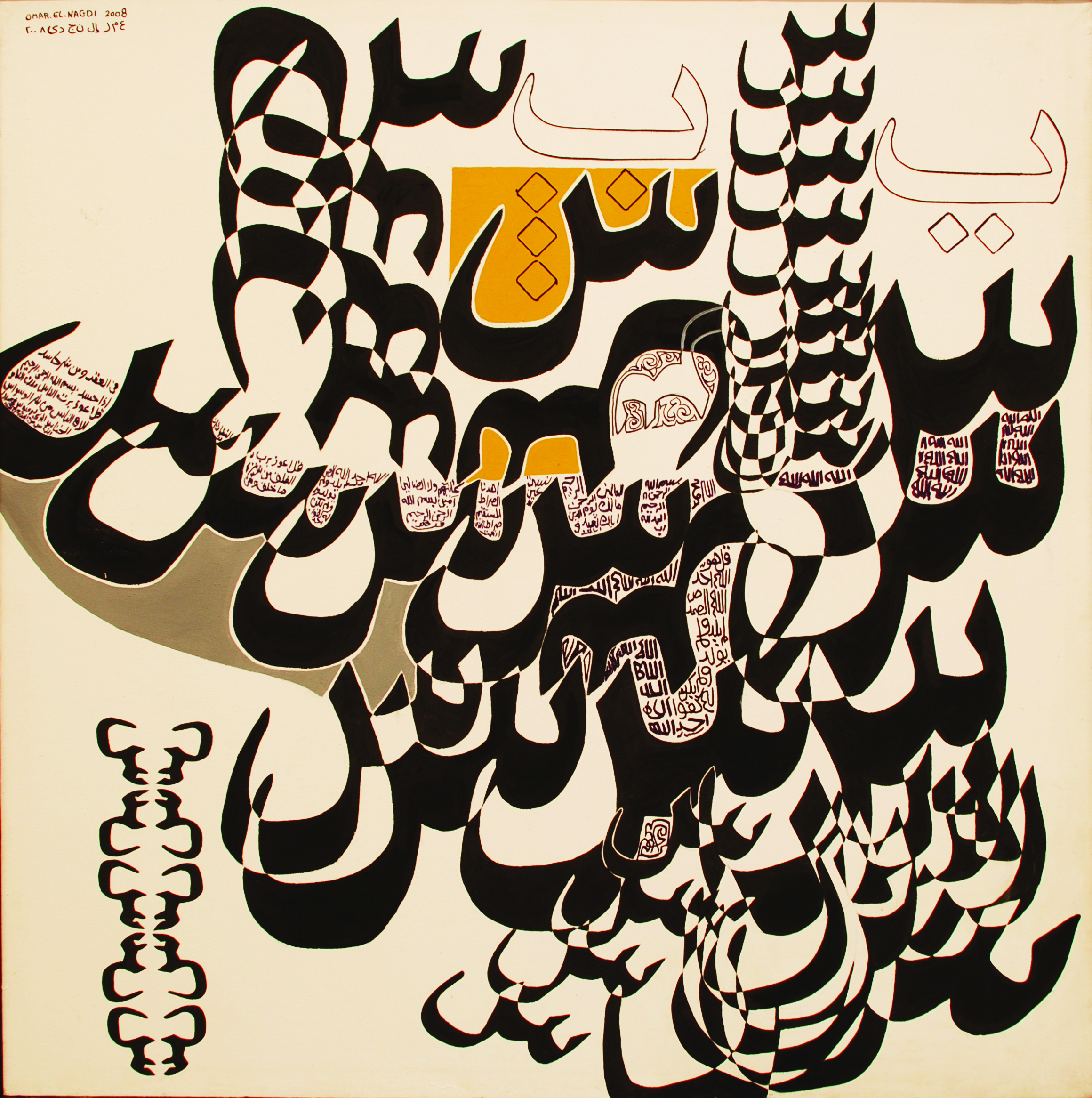

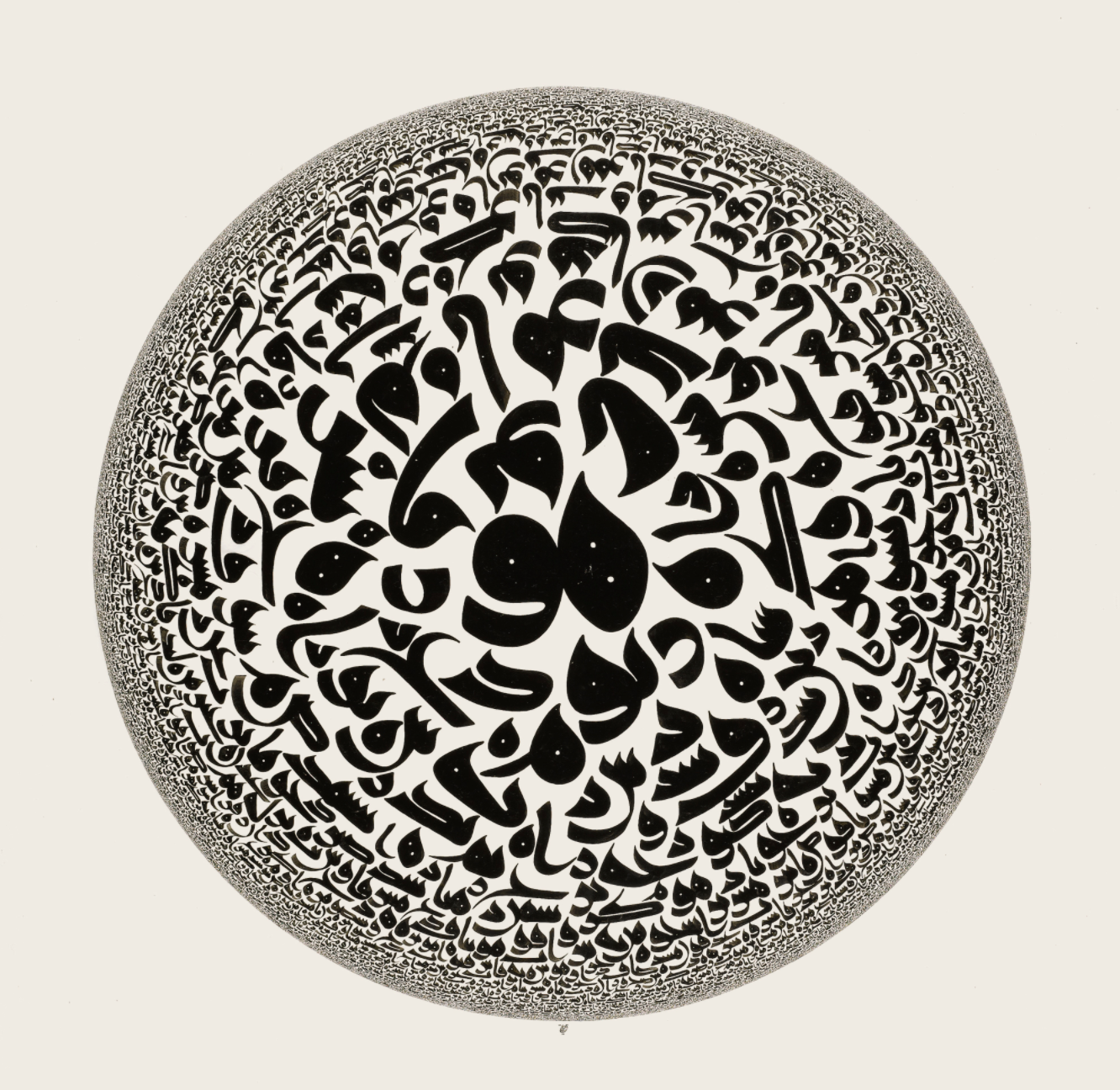

Shirin Neshat’s artistic career is particularly noteworthy in that it has brought to light the time-honoured artistic and literary traditions of the Middle East, through a contemporary lense. Intimately tied with religion, Islamic art has focused on the depiction of patterns and Arabic calligraphy to depict the divine. Egyptian artist Omar El Nagdi’s “Untitled,” is a similar experimentation with calligraphy and religious representation. His works employ singular Arabic words, such as ALLAH and the Arabic numeral one repeating, the artist attempts to emulate the motion of the whirling dervishes and their Sufi practice. And yet, an aesthetic of modernity permeates these works. Iranian artist Azra Aghighi Bakhshayeshi is the descendent of the famous court calligrapher Mirza Karim Khoshnevish Tabhari, and the only professional female calligraphic artist working in Iran. Her work explores the rich aesthetic possibilities inherent in the internal architecture of Persian script. As with many calligraphic artists of global origins, Azra sees beauty not simply in the meaning of letters but in the texture and form of writing.

“When viewers do not understand the meaning they are not reading the letters. I am looking for viewers who are seeing and not reading. These writings are whispers in my mind that do not mean too much, like a meditation. Sometimes they could be poetry, prayers, or just a conversation. I am not trying to convey spirituality with my writings. Speaking only one language creates a barrier between me and the viewer if they do not speak the same language. I am hoping to reach out to a broader audience with my art as a universal message.” –– Azra Aghighi Bakhshayeshi (Source)

In a vernacular daily life, hand-lettered calligraphy continues to be valued in letters and invitations, font design and typography, religious art, graphic design, and memorial inscriptions. But has modernity cast aside calligraphy as a creative practice? The enduring popularity of these myriad contemporary artists seems to indicate a deep influence of calligraphic traditions on the cultural production of today. When we put pen to paper, on the fewer occasions that it is necessary nowadays, we conjure a profound history of creative spirit. What a gift it is to participate in the tactile handwritten tradition, in the alchemical meeting of ink and paper––do we recall this art form as we compose our daily emails?

- References:

- https://www.thebroad.org/art/shirin-neshat

- https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/the-art-of-calligraphy

- https://www.christies.com/features/Expert-guide-to-Chinese-calligraphy-9727-1.aspx

- http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20130408000852

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-FYX_EiFWW8&ab_channel=FarhangFoundation

- https://www.kashyahildebrand.org/zurich/bakhshayeshi/bakhshayeshi002.html

- http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20130408000852

- https://www.pinterest.com/pin/225531893826111587/

- http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/lot.71.html/2011/contemporary-art-arab-iranian-l11225

- https://blantonmuseum.org/exhibition/xu-bing-book-from-the-sky/

- https://www.christies.com/lot/lot-wang-dongling-b-1945-su-shi–5998405/

- https://www.artsy.net/artwork/willem-de-kooning-untitled-79

- https://www.google.com/search?q=saburo+hasegawa+four+poem+drawings&sxsrf=ALeKk00CHWxsG7yLRvQEVjuF5BoAgBDoVg:1606073937311&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjGr5DU85btAhUBvFkKHQEZBwoQ_AUoAXoECAsQAw&biw=1432&bih=656