According to Aristotle, “No great mind has ever existed without a touch of madness.” The great Georgia O’Keeffe’s dreamy close-up still-life and landscape paintings hardly bespeak her lifetime of anxiety and depression, weeping spells and long periods without eating or sleeping. The great composer Schumann believed that Beethoven was channeling musical inspiration to him from beyond the grave. Charles Dickens lived his life believing he was being followed by the characters from his novels. Emily Dickinson, Nikola Tesla, and Isaac Newton exhibited social anhedonia: a consistent preference for solitary activities and work over socializing. Famous authors and poets Sylvia Plath, Edgar Allen Poe, and Virginia Woolf are known to have suffered from bipolar disorder.

Albert Einstein, the world’s most famous and beloved “mad scientist.”

The “mad artist” archetype dates as far back as ancient Greece, where both Plato and Aristotle made comments about the peculiar behavior of poets and playwrights. Fast forward to present day, where clinical researchers around the world are fascinated by the mental states of the greatest creatives: what genetic variants mark a person for genius, exceptional outside-the-box thinking and “aha!” moments? Can modern science crack the case of the origins of exceptional creativity in the human mind?

The association between creativity and mental health seems to be substantiated by modern research, and often picked up by popular press. A study in 2009 done by Szabolcs Keri, a researcher in the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy at Semmelweis University in Budapest, Hungary, concluded that “genetic polymorphisms related to severe mental disorders” were found in people with the “highest creative achievements and creative-thinking scores.” Studies from the Karolinska Institute found writers have a higher risk of suffering from anxiety, schizophrenia and substance abuse. Frighteningly, they concluded that writers were 121% more likely to be bipolar, as well as 50% more likely to commit suicide.

Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama in her 2013 solo exhibition “I Who Have Arrived in Heaven” at David Zwirner, New York.

In recent years, Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama has risen to legendary stature as arguably the world’s most popular contemporary artist. Known during the 1960s for her reign as the Polka-Dot Priestess of the countercultural movement, Kusama trademark of polka-dots adorn installations, paintings, sculptures and now even Louis Vuitton handbags. Her “Infinity Rooms,” in which mirrors repeat lights and landscapes infinitely, generate throngs of viewers and massive lines. Yet Kusama attributes her obsession with repetition and pattern to recurring hallucinations she has had since childhood. Her neurological disorder is termed Visual Snow Syndrome, characterized by continuous visual disturbances of white or black dots occupying the person’s visual field. Kusama returned to her native Japan in 1973 and was diagnosed with rijinsho—literally, “separate-person syndrome.” She experienced frequent hallucinations and severe depression. In 1977, when her neurosis became unmanageable, she checked herself into a mental hospital, where she has lived ever since. Kusama says she also suffers from obsessive-compulsive disorder and must visit her studio every day to paint in order to stay sane.

Kusama in her studio, with infinite dot paintings.

As a Japanese woman artist in a white male-dominated Pop Art scene, Kusama “displayed herself as a weaker, mentally-ill figure, which allowed her to enter into the art scene,” according to Japanese art historian Midori Yamamura. Thanks to this calculated curation of her identity, Kusama was accepted by the avant-garde; in some ways, Kusama used her reputation with mental illness to her advantage, generating buzz around her work. Still, for years her minority status prevented total equality with her white male peers, and her paranoia worsened as the likes of Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg appropriated her visual language.

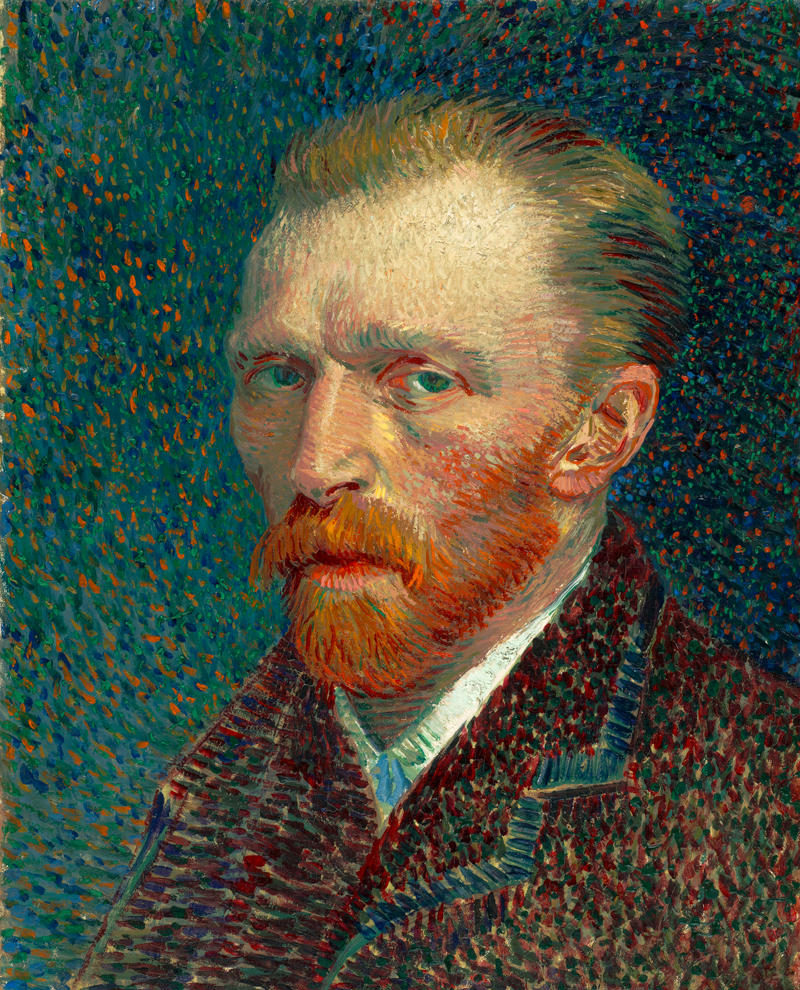

Vincent Van Gogh, Self-Portrait (1887), oil on artist’s board.

Many have drawn the connection that Yayoi Kusama’s life seems to closely mirror another iconic artist a hundred years her senior: Vincent Van Gogh. “I put my heart and my soul into my work, and lost my mind in the process,” he famously declared. Van Gogh’s post-impressionist paintings are beloved in large part due to his understanding of color theory, which he describes in many letters to his brother Theo. Van Gogh spent his lifetime studying theoretical principles of colors, mixing colors, intensity and tonal values. As such he had extraordinary insight into the potential for color pairings to intensify one another: Which color combinations create the most powerful effect? How many variations are there of a single color? He wrote to Theo in a letter from July 1882:

“There are three basic colours: red, yellow and blue. These three colours are all that are needed to be able to represent nature. However, it is essential that the painter adds black to them … Black may thus be considered, in the variety of its shades, as the basis of all the colorations nature presents.”

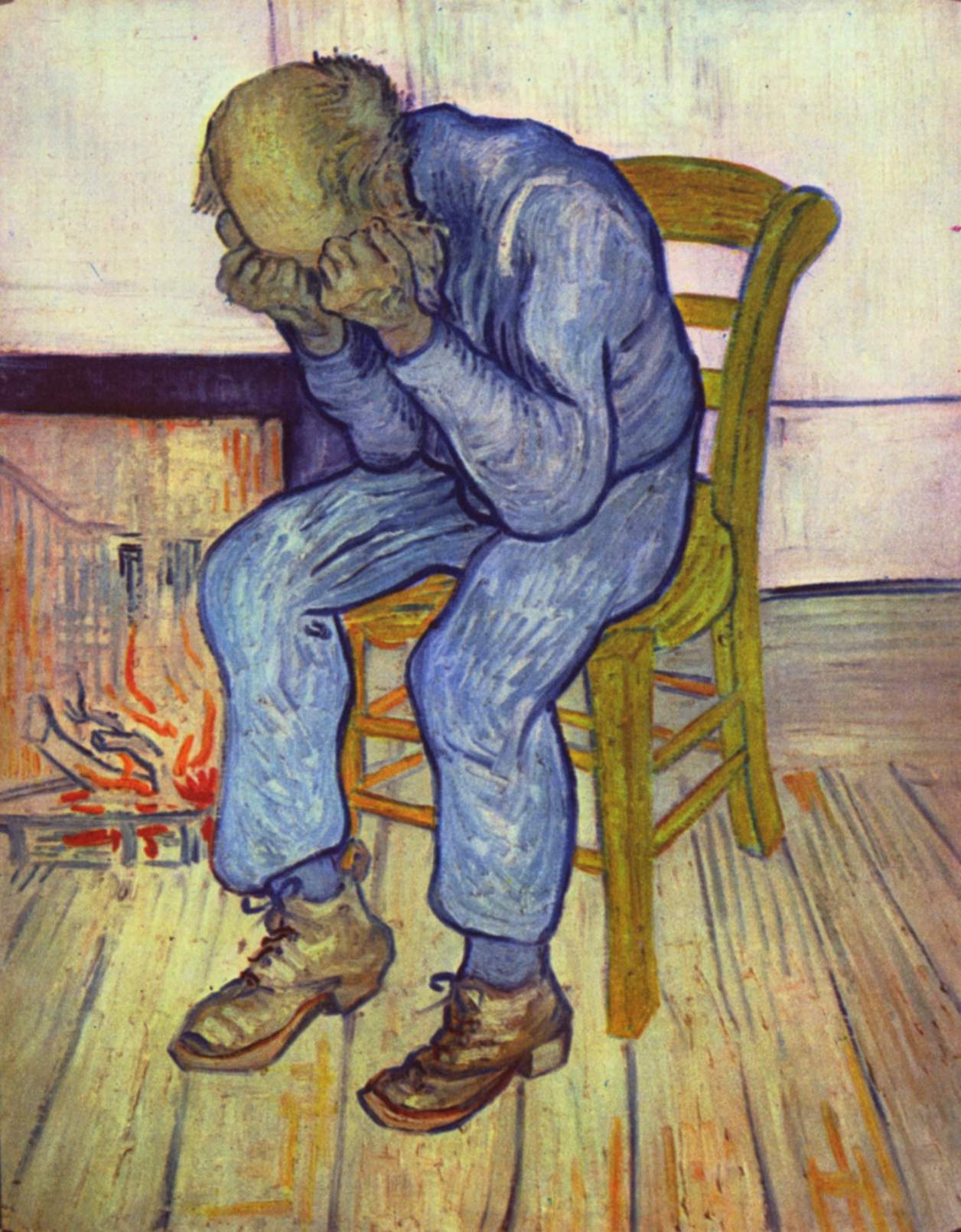

Indeed, Van Gogh’s color palettes showcase his intimate understanding of the powers of vibrant tones and intense contrasts. He was equally talented as he was troubled, however, and suffering from depression, acute mania, anxiety, and bipolar disorder throughout his life. In fact, he is perhaps as well-known for his paintings as he is for infamously cutting off a piece of his own ear in a fit of mania and mailing it to his lover. A thoughtful and sensitive person, Van Gogh was often ridiculed and mistreated throughout his lifetime. One of western art history’s most famous paintings, Van Gogh’s “Starry Night,” depicts the view from his window of the asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence that he admitted himself to. Extreme creativity and insight often come at a hefty price.

Vincent Van Gogh, Sorrowing Old Man, 1890, oil on canvas.

As it would appear, highly creative thinking is intrinsically tied to deviant behavior psychological abnormality. In 2016, a group of researchers reported on the “psychopath model of the creative personality” in the journal Personality and Individual Differences. An even more detailed study was published in 2011 by Shelley Carson, Harvard lecturer and researcher in creativity and abnormal psychology, titled “The Unleashed Mind,” with the subtext: Highly creative people often seem weirder than the rest of us. Now researchers know why.

To sum it up in more clinical language, she writes in a chapter of James Kaufman’s 2014 The Shared Vulnerability Model of Creativity and Psychopathology: “In general, research indicates that creative people in arts-related professions endorse higher rates of positive schizotypy than non-arts professionals.” By positive schizotypy, Carson means that eccentric people may inherit the unconventional modes of thinking and perceiving associated with schizophrenia without inheriting the disease itself.

As such, both creativity and eccentricity may be the result of genetic variations that increase cognitive disinhibition—the brain’s failure to filter out extraneous information. Cognitive disinhibition is the failure to ignore information that is irrelevant to current goals or to survival. When this unfiltered information reaches conscious awareness in the brains of people who are highly intelligent and can process this information without being overwhelmed, it may lead to exceptional insights and sensations. People who have increased cognitive disinhibition, and incidentally also score high for creative achievement in the arts, are much more likely to believe in paranormal phenomena like telepathic communication, prophetic dreams, divination, and past lives. Reduced cognitive filtering could explain the tendency of highly creative people to focus intensely on their inner world at the expense of social and even self-care needs. Carson concludes that reduction in cognitive inhibition allows more material into conscious awareness that can then be reprocessed and recombined in original ways, resulting in exceptionally creative ideas.

Yet, reduced cognitive inhibition, schizophrenia, and psychosis are considered biological vulnerability factors, and these gene variations cause psychotic illnesses. Highly-funtioning and neurotypical people have biological makeups that shield them from mental illness. Creative eccentrics sit at a middle-ground between the two, with high IQ and memory capacity that shields them from being completely overwhelmed by bizarre thoughts and sensations and allow them to use those stimuli as inspiration for great works of art.

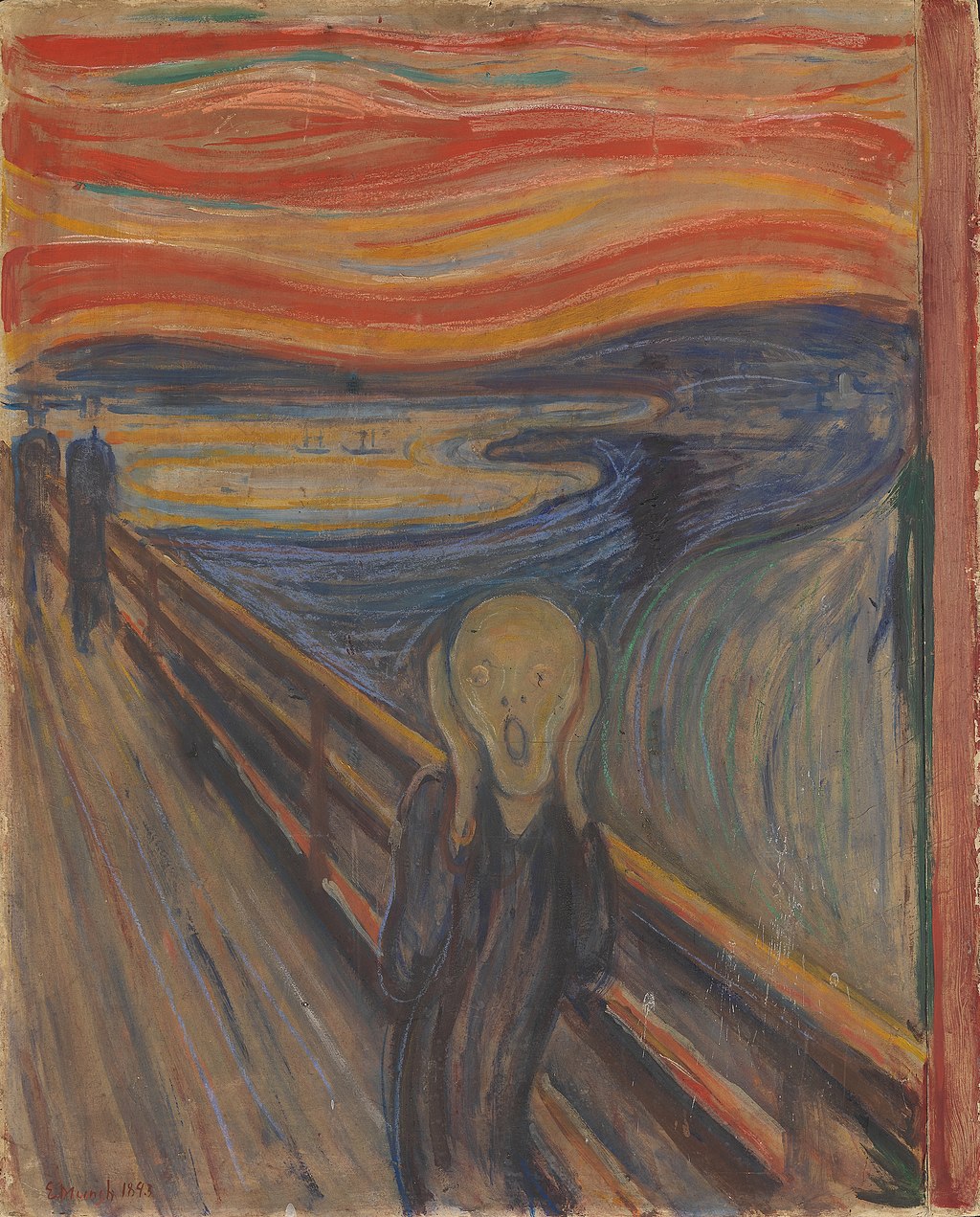

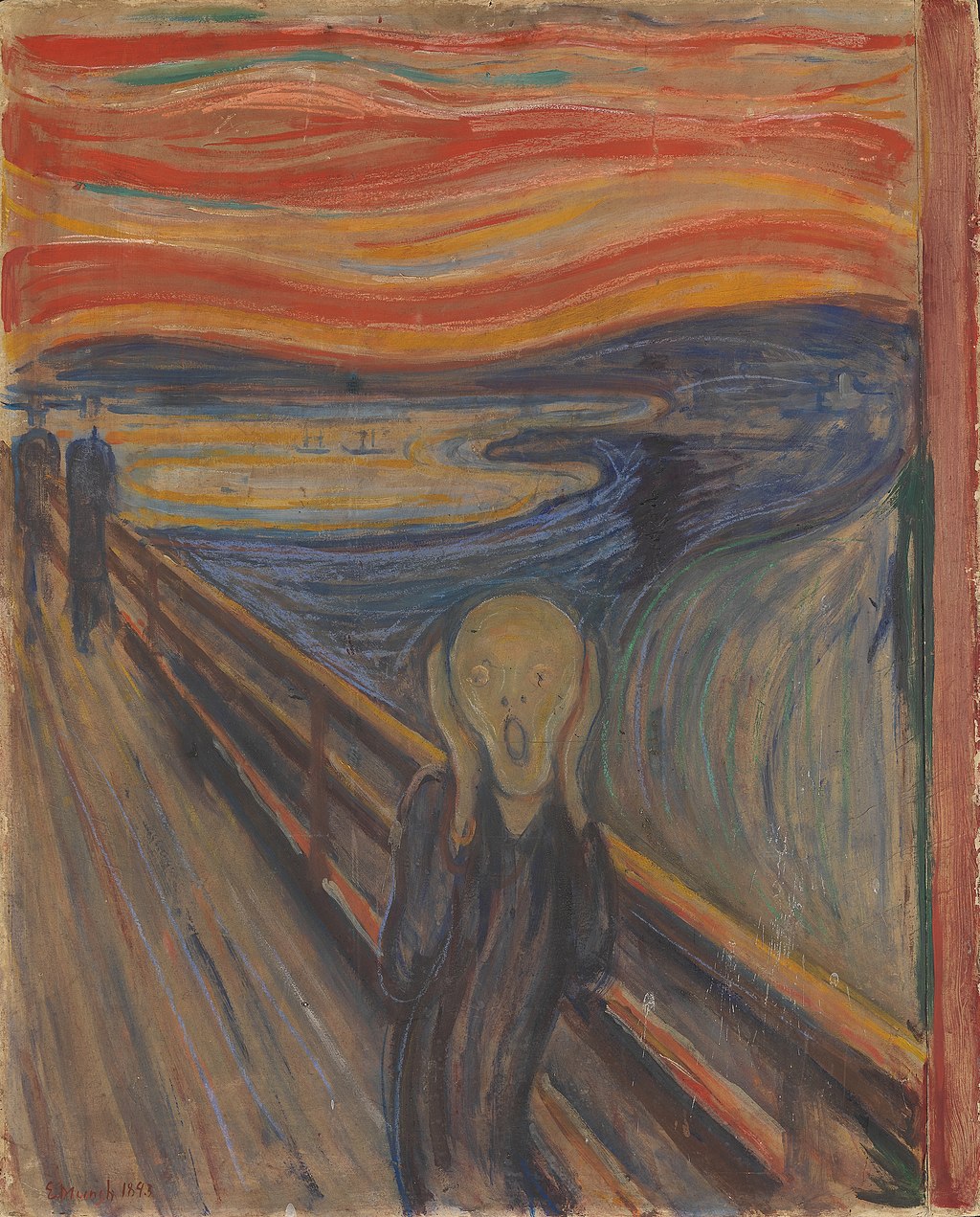

Edvard Munch, The Scream (1893) oil, tempera, pastel, and crayon on cardboard.

Edvard Munch was one such artist whose artwork exuded his own internal suffering: his infamous painting The Scream was inspired by an evening walk in which the sky began to turn blood red and he felt an attack of anxiety, hallucinating an “infinite scream” resonate through nature. Another painting from 1894 titled Anxiety, takes place in the same setting as The Scream. The Norwegian artist wrote in his journal,

“My fear of life is necessary to me, as is my illness. Without anxiety and illness, I am a ship without a rudder … my sufferings are part of my self and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art.”

He observed, “Illness, insanity and death were the black angels that kept watch over my cradle and accompanied me all my life.” Throughout his lifetime, Munch was plagued by anxiety and hallucinations, and a negative relationship with women that manifested itself in numerous succubus and vampiric portraits.

Munch’s emotionally-charged paintings act as portals into his inner world and his experience with anxiety: a powerful tool in understanding his personal challenges. Our world continues to benefit from the work of creatives, allowing us to experience, think, and emote in more profound ways. While the several aforementioned studies place the instances of cognitive disinhibition, psychosis, and schizophrenia at the heart of creativity and insight, it should be understood that most people suffering from these disorders do not produce ideas that are considered creative, however. The ability to use cognitive disinhibition in a creative way depends on the presence of additional cognitive abilities associated with a high level of functioning. And still, some relatively normal personality traits are also highly predictive of creativity; such as openness to experience and problem-solving.

Vincent Van Gogh, Starry Night (1889), oil on canvas.

And yet, we should take seriously mental illness and disorders, and be wary not to glamorize the often-debilitating experiences of others. New discoveries in the mental states of highly-creative people invite us to empathize with varied human experiences and psychological differences. Instead of ostracizing eccentric personalities and psychological abnormalities, scientific breakthroughs in creativity and psychology can create a culture of acceptance and value of difference–how’s that for an earful?