Time: without exception, the enemy of all the world’s great art and cultural artifacts. This means time in the physical, literal sense: the degradation of media which all museum and conservation entities seek to curtail. But we also mean time in its associative senses: what sorts of political climates is art subjected to throughout its lifetime and what do “the times” dictate about our attitudes towards art? Often the masterpieces in our museums have seen more of the world and all of its changes than we have.

And yet, some art does not make it here: by definition, lost artworks are original pieces of art that credible sources indicate once existed but that cannot be account for in museums or private collections, or are known to have been destroyed deliberately or accidentally, or neglected through ignorance and lack of connoisseurship. What does the world and its people lose when its artistic objects are lost, stolen, or destroyed?

The US FBI maintains a list of “Top Ten Art Crimes”; a 2006 book by Simon Houpt and several other media outlets have profiled the most significant outstanding losses. The U.S. has its own Art Loss Registry. Art loss events have been chronicled as far back as the 226 BCE Rhodes Earthquake to the National Museum of Brazil fire in September 2018. It’s both a fascinating and mournful topic.

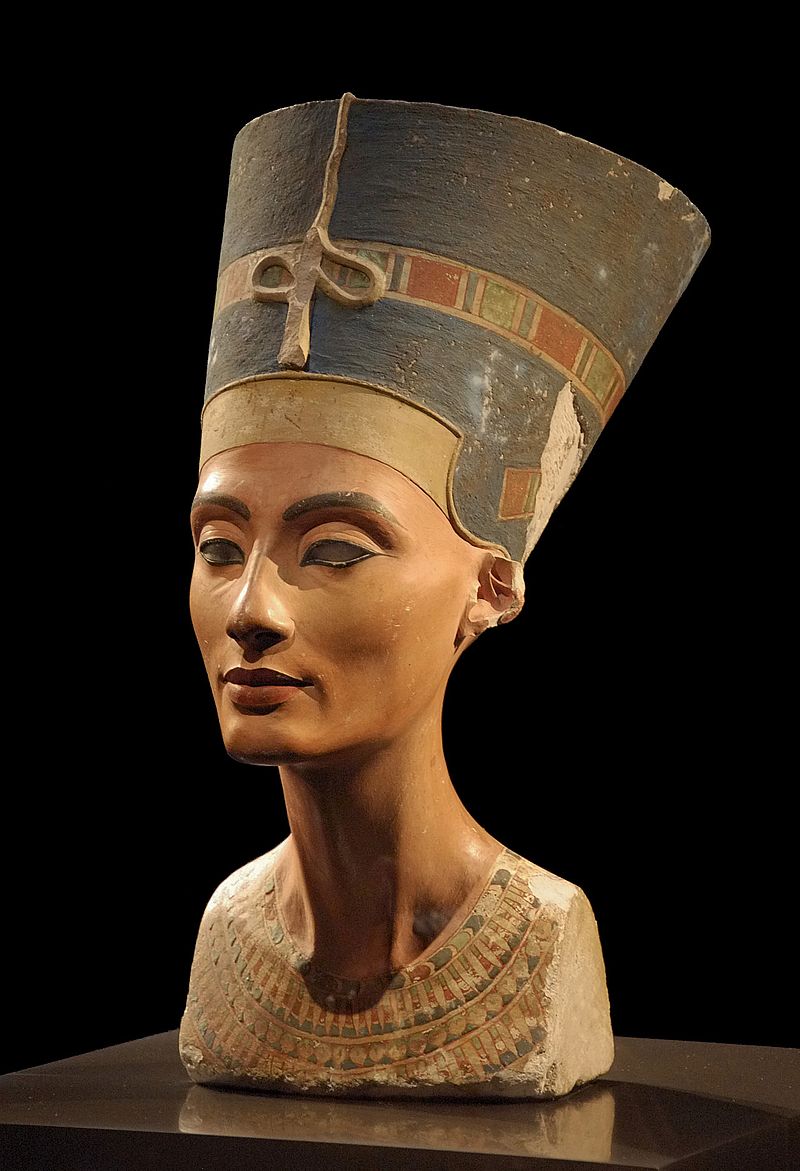

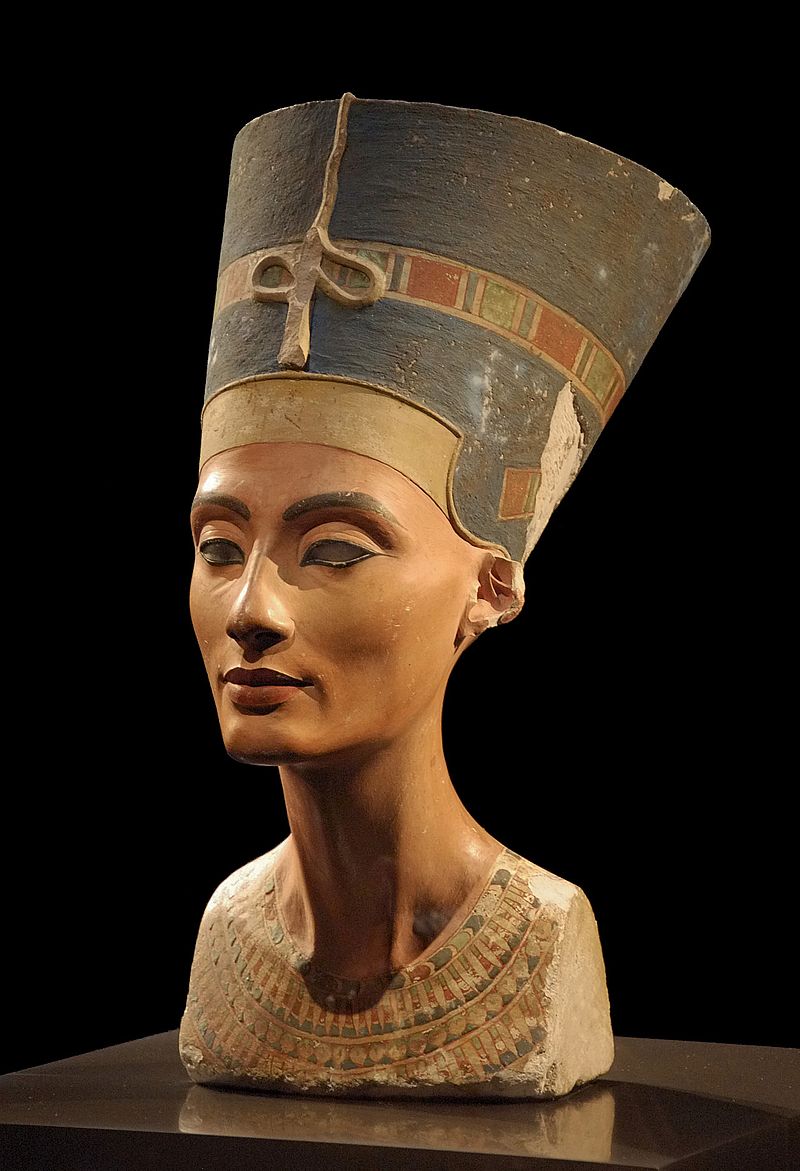

Image of the Nefertiti Bust, a painted stucco-coated limestone. Nefertiti was the Great Royal Wife of Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten, and her bust is the most widely copied artwork of ancient Egypt.

In the hot, wind-swept desert of Egypt in 1912, German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt unearthed a stunning artifact that would shock the world: Nefertiti’s Bust, the famous 14th century Egyptian queen with arresting beauty and immense power. He justified the acquisition of this most-prized find through an agreement with Egyptian officials that included rights to half of his finds, but intentionally misled authorities with poorly-lit photos and underreporting its composition. When the iconic bust, created in limestone in 1340 BC, was unveiled at the Neues Museum in Berlin in 1924, calls immediately rang in demanding its return to Egypt. In the early 1930s, movements were made to return the Queen to Egyptian authorities, but with the onslaught of World War II and Hitler’s regime, these plans have still never come to fruition.

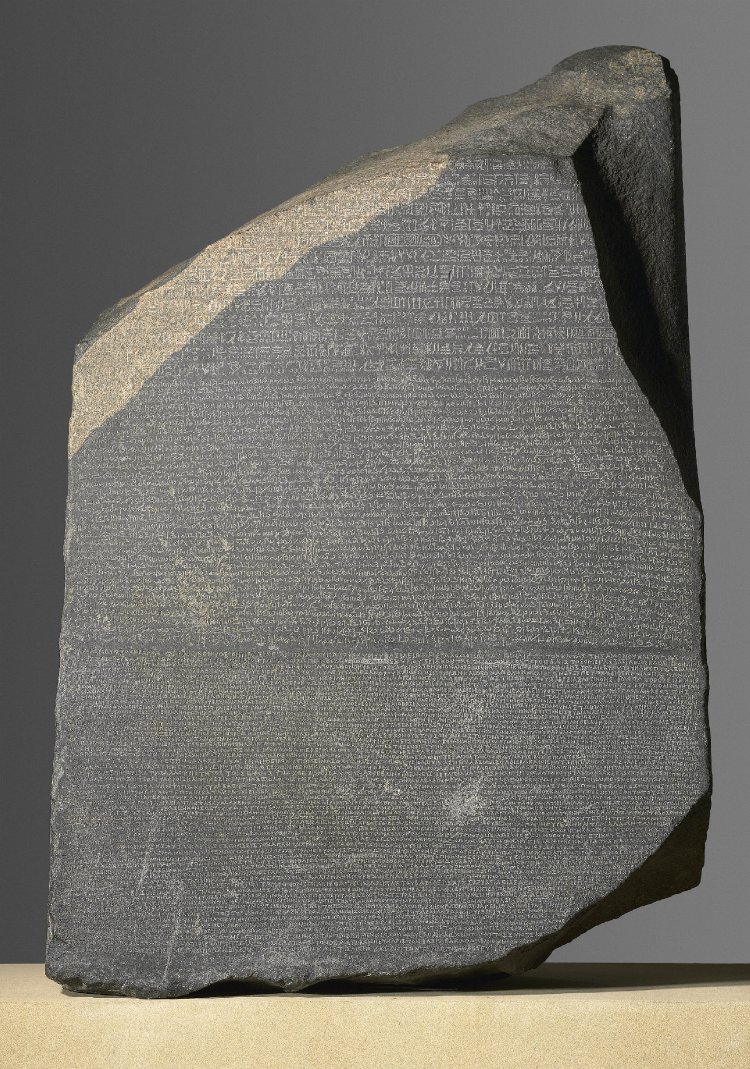

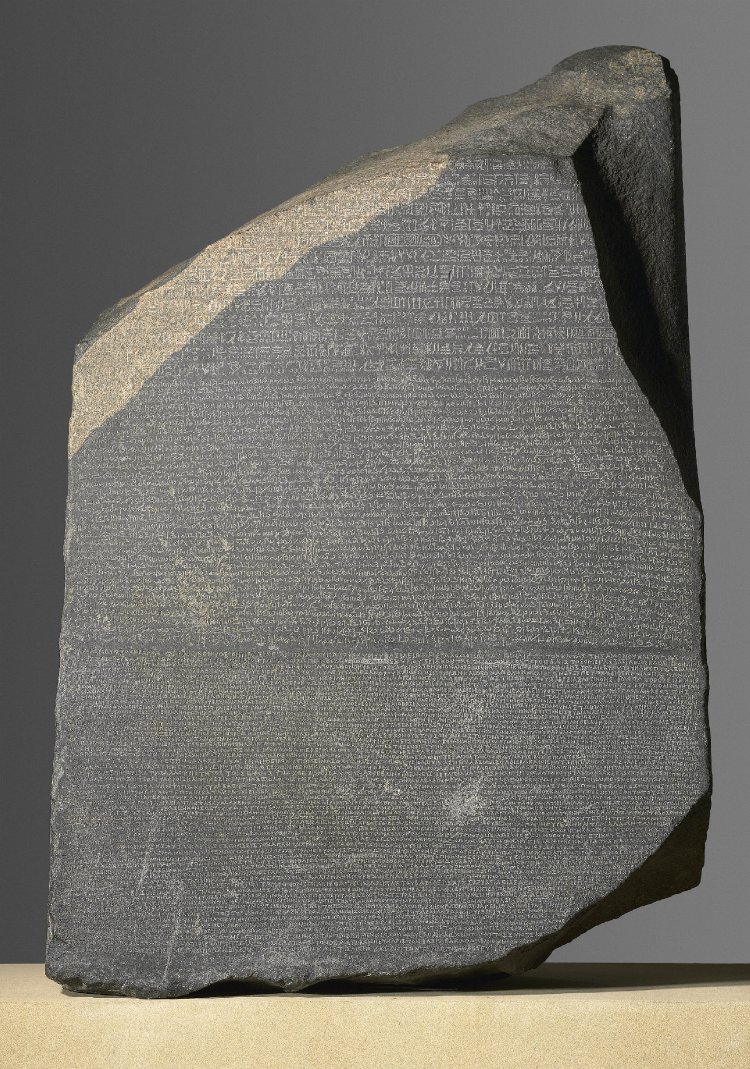

The famed Rosetta Stone, an ancient royal decree written in three different writing systems, which allowed researchers to finally decode Egyptian hieroglyphs by reading it alongside its ancient Greek inscription.

Often art loss is tied in with repatriation and cultural seizure. Even today, some of the most esteemed cultural institutions are grappling with the shady provenance of stolen and seized artifacts. Countries like Egypt and Greece, with highly-valuable ancient art, have made reclaiming cultural artifacts a top priority in recent years. The high-profile Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass led aggressive efforts as Egypt’s Minister of Antiquities to reclaim antiquities stolen from the country and purchased by leading world museums. One of the most high-profile cases was Egypt’s demand that the Rosetta Stone be returned from the British Museum after 200 years of its seizure. The ancient slab, engraved with an identical message in Ancient Greek, Demotic and Egyptian hieroglyphs, allowed 19th century scholars to translate the hieroglyphs, and serves as an ancient treasure for global historians and linguists. British soldiers captured the stone in 1801 after defeating Napoleon’s army in Egypt, then transferred it to the British Museum as conquest. Egyptian officials for decades demanded the return of the ill-gotten Rosetta Stone, but because it has long been the museum’s most-visited object, they continue making demands to seemingly deaf ears. The institution justifies their ownership of items like the Rosetta Stone by stating that it “[allows] a global public to examine cultural identities and explore the complex network of interconnected human cultures” within the galleries, said a spokesperson from the British Museum.

Many UK museums continue to hold troubling inheritances from their imperialist past, especially 19th century conquests. Objects such as the Maqdala Treasures, seized in a military campaign against the Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia in 1868, continue to be displayed in the British Museum, British Library, and the Victoria & Albert Museum. And don’t even get us started on the Elgin Marbles.

The Zodiac of Dendera, a controversial Egyptian bas-relief owned by the Louvre.

Britain’s museums hold a troubling inheritance from the 19th century, a period in which British troops captured cultural property and burned entire cities to the ground. Objects such as the Maqdala Treasures, seized in a military campaign against the Ethiopian Emperor Tewodros II in 1868, now sit in the galleries and storerooms of the British Museum, the British Library and the Victoria & Albert Museum. They may no longer be displayed proudly as trophies of war, but there are increasingly urgent calls for their repatriation.

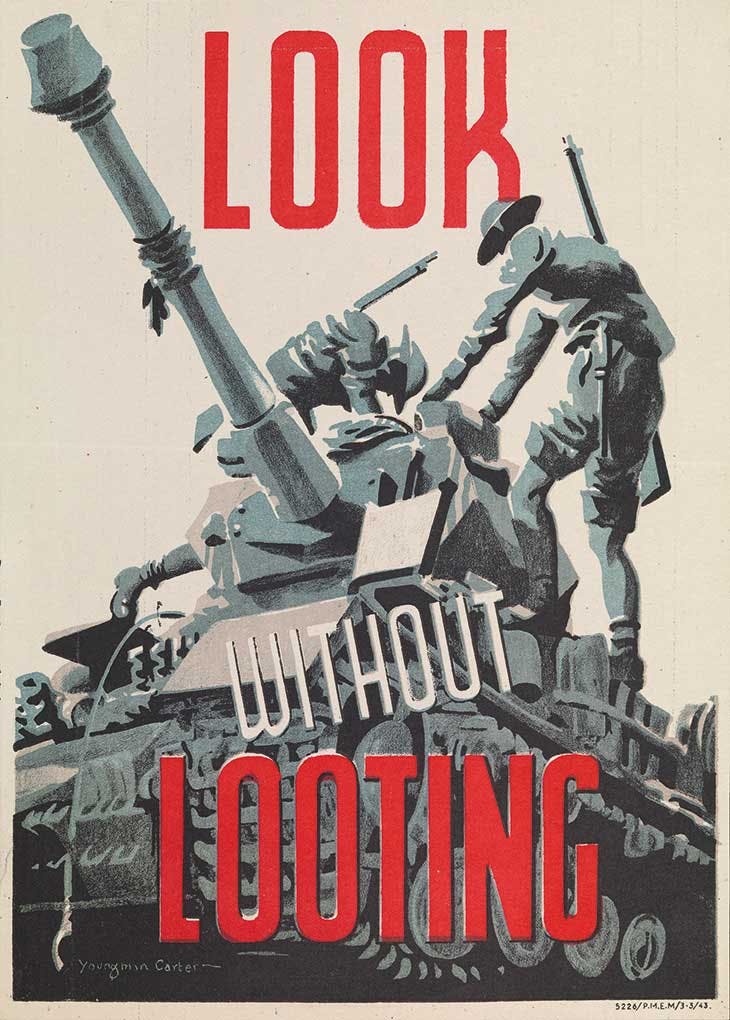

Look without Looting (1943), poster designed by Philip Youngman Carter for the British Army. Imperial War Museum, London.

In addition, Zahi Hawass made claims that the Louvre had bought priceless Egyptian mural fragments despite knowing they were taken from a tomb in Egypt’s storied Valley of the Kings in the 1980s, a prime spot for grave-robbers. The provenance of these frescoes was called into question after the discovery of the tomb from which they were believed to have been stolen. Egypt’s Supreme Council for Antiquities suspended cooperation with the Louvre until the issue was resolved, and in 2009 the Louvre announced that they had agreed in considering the logistics in this move.

Shaaban Abdel-Gawad, Head of the Egyptian Department of Repatriation, with Nedjemankh’s Coffin.

Often, stolen or lost artifacts move through many hands and have become massive investments by the time they are discovered. In 2019, the Metropolitan Museum of Art successfully reinstituted a gilded Egyptian coffin inscribed with the name Nedjemankh, a priest of the god Heryshef, to Egypt after it learned that the piece was stolen in 2011. A New York Times article alleged that the Met had paid about $4 million for the sarcophagus, and though reluctant, eventually ceded the object with plans to regain the funds elsewhere.

During the case of Nedjemankh’s coffin, the Met spokespersons claimed that all of their acquisitions were made “in recognition of the 1970 UNESCO treaty, in adherence to the Association of Art Museum Directors’ Guidelines on the Acquisition of Ancient Art and Archaeological Materials, and in compliance with federal and state laws.” Under the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) convention of 1970, countries agreed to complex measures to prevent the illegal export of national treasures, which include performing “due diligence” in verifying the provenance of historic objects. But of course, much is at stake, and illegal markets, fraudulent documentation, conflicting interests, and the temptation of ownership can be difficult to navigate.

“After we learned that the Museum was a victim of fraud and unwittingly participated in the illegal trade of antiquities, we worked with the DA’s office for its return to Egypt,” the Met’s president and CEO, Daniel Weiss, said. “The nation of Egypt has been a strong partner of the museum’s for over a century. We extend our apologies to Dr. Khaled El-Enany, minister of antiquities, and the people of Egypt, and our appreciation to District Attorney Cy Vance, Jr.’s office for its investigation, and now commit ourselves to identifying how justice can be served, and how we can help to deter future offenses against cultural property.”

We are considerably lucky that these ancient objects have even survived the centuries of degradation to be studied and appreciated today. However, the contemporary world has known far too many cases of “cultural annihilation,” brought on by religious or political extremism and terrorism. The entire globe was shocked and outraged when in 2001 a fleet of Taliban fighters led by extremist leader Mullah Mohammed Omar in Bamiyan Valley, Afghanistan destroyed two monumental sandstone statues of the Buddha dating back to the 6th century with explosives, claiming their existence was anti-Islamic. The Bamiyan Buddhas were an expression of the early Buddhism that flourished in Afghanistan; the statues gazed down on carrivaners on the Silk Road, and long represented the confluence of spiritual ideologies, as well as Greco-Indian art, blending artistic traditions of India with stylistic ancient Greece touches.

One of the Bamiyan Buddha statues in Afghanistan.

Now merely two gaping niches in the mountainside, archaeologists and Unesco-policy makers debate how to best rebuild. In the meantime, Chinese documentarian couple Janson Yu and Liyan Hu have instituted a $120,000 3D projection device that casts hologram recreations of the statues to size where the original statues once stood, an appropriate solution in the valley whose name translates in Persian to “the place of shining light.” Unesco has declared the whole valley, including the more than half-mile-long cliff and its monasteries, a World Heritage Site. Locals survey the empty holes in the mountainside with remorse and tremendous loss, but hope they will stand as a warning against the ignorance of religious intolerance for future generations.

Locals walking past the empty niche where the Bamiyan Buddha once stood.

Of course, the Bamiyan Buddhas are far from the only great cultural losses at the hands of political or religious extremism. In 1975 Cambodia, the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime “began decimating that country’s ancient sites in search of treasures to sell on the international art market,” Tess Davis, executive director of Washington, DC-based Lawyers’ Committee for Cultural Heritage Preservation, wrote for the LA Times.

“Monuments Man” James Rorimer, with notepad, supervises U.S. soldiers as they carry paintings down the steps of the castle in Neuschwanstein, Germany, in May 1945.

And nearly most infamous of all was the Nazis: The Third Reich’s reign from 1933 to 1945 saw the seizure of some 600,000 paintings, with at least 100,000 still missing. The large-scale looting was conceived to bolster the Third Reich in addition to eliminating all vestiges of Jewish identity and culture. The systemic looting, especially of Warsaw, Poland, by the Nazis during World War II still resonates today in that country, where officials continue to seek 63,000 missing works of art. Despite positive forces like the art expert “Monuments Men” (with a great film of the same name) in the liberating U.S. army seeking to stack down stolen art, most artwork remains lost to their rightful owners. In 1998, Forty-four major countries agreed to the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art, an agreement that called for a “just and fair solution” for Jews and other victims of Nazi persecution.

American soldiers recovering German loot stored in a Church at Elligen, Germany.

In Vienna, some Nazi plunder, such as Gustav Klimt’s famous 2007 Woman in Gold painting titled “Adele Bloch-Bauer I,” had been hanging in a gallery when finally found and restituted. This particular masterpiece was reclaimed by the niece of “Adele Bloch-Bauer I,” Maria Altmann, who took on the uncooperative Austrian government. The Austrian angle was that the subject of the painting, Ms. Bloch-Bauer herself, left the portrait to the country in her will before dying of meningitis in 1925. However, after a long and arduous battle, records revealed that the artwork actually belonged to her husband, a wealthy Jewish industrialist Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, who left his entire estate to his heirs––one of whom was Ms. Altman, his niece.

Maria Altmann with “Adele Bloch-Bauer I,” also known as “Woman in Gold.”

This story of lost and stolen artwork, and the journeys they endure, strikes a chord with so many: these are stories rife with mystery, intrigue, outrage, and the potential for great justice. It is such an interesting topic that countless movies have even been made on the subject: George Clooney’s movie “Monuments Men,” for instance. And Simon Curtis’ 2015 film “Woman in Gold” actually traces Ms. Altman’s heroic story.

Franz Friedrich (“Fritz”) Grünbaum.

Another case involved popular Viennese cabaret performer, Fritz Grünbaum, whose 400-work art collection––which included 81 works by Egon Schieles such as “Woman in a Black Pinafore” and “Woman Hiding Her Face,”––was inventoried and seized by Nazi agents in 1938. Fritz Grünbaum was a prominent anti-Nazi at the time, and was sent to a concentration camp where he put on performances openly mocking Hitler and the Third Reich. Following his death, Grünbaum’s heirs have been disputing its private possession and by 2018 a New York State Supreme Court judge, Charles J. Ramos, found the heirs’ arguments persuasive and that the Grünbaum collection had indeed been looted by Nazis. Finally, the court ordered one of the collection’s dealers, Richard Nagy, to return Schiele’s “Woman in a Black Pinafore” and “Woman Hiding Her Face” to them––the first step in a hard legal battle for restitution still being waged today.

Egon Schiele, “Woman in Black Pinafore,” 1911.

Egon Schiele, “Woman Hiding Her Face,” 1912.

The challenges we face in preserving, protecting, and repatriating great works of art reveal uncomfortable truths about our human societies, as well as areas for improvement. The empty niches of the Bamiyan Buddhas, for instance, warn us today of humanity’s potential for destruction and the dangerous disregard for history that comes with it. And yet, Maria Altmann finally winning back her family’s beloved art collection is a testament to the changes in our attitudes. Who does art belong to and for what purpose does it serve to the possessor? What is the cost when we lose the world’s great cultural artifacts, and how do we best protect and appreciate them? As more questions arise, so too will new answers inevitably and always prevail.